America 's Muslims Aren't as Assimilated as You Think

By Geneive Abdo

Washington Post, August 27, 2006

If only the Muslims in Europe -- with their hearts focused on the Islamic world and their carry-on liquids poised for destruction in the West -- could behave like the well-educated, secular and Americanizing Muslims in the United States , no one would have to worry.

So runs the comforting media narrative that has developed around the approximately 6 million Muslims in the United States, who are often portrayed as well-assimilated and willing to leave their religion and culture behind in pursuit of American values and lifestyle. But over the past two years, I have traveled the country, visiting mosques, interviewing Muslim leaders and speaking to Muslim youths in universities and Islamic centers from New York to Michigan to California -- and I have encountered a different truth. I found few signs of London-style radicalism among Muslims in the United States . At the same time, the real story of American Muslims is one of accelerating alienation from the mainstream of U.S. life, with Muslims in this country choosing their Islamic identity over their American one.

A new generation of American Muslims -- living in the shadow of the Sept. 11, 2001 , attacks -- is becoming more religious. They are more likely to take comfort in their own communities, and less likely to embrace the nation's fabled melting pot of shared values and common culture.

Part of this is linked to the resurgence of Islam over the past several decades, a growth as visible in Western Europe and the United States as it is in Egypt and Morocco . But the Sept. 11 attacks also had the dual effect of making American Muslims feel isolated in their adopted country, while pushing them to rediscover their faith.

From schools to language to religion, American Muslims are becoming a people apart. Young, first-generation American Muslim women -- whose parents were born in Egypt, Pakistan and other Islamic countries -- are wearing head scarves even if their mothers had left them behind; increasing numbers of young Muslims are attending Islamic schools and lectures; Muslim student associations in high schools and at colleges are proliferating; and the role of the mosque has evolved from strictly a place of worship to a center for socializing and for learning Arabic and Urdu as well as the Koran.

The men and women I spoke to -- all mosque-goers, most born in the United States to immigrants -- include students, activists, imams and everyday working Muslims. Almost without exception, they recall feeling under siege after Sept. 11, with FBI agents raiding their mosques and homes, neighbors eyeing them suspiciously and television programs portraying Muslims as the new enemies of the West.

Such feelings led them, they say, to adopt Islamic symbols -- the hijab , or head covering, for women and the kufi , or cap, for men -- as a defense mechanism. Many, such as Rehan , whom I met at a madrassa (religious school) in California with her husband, Ramy , also felt compelled to deepen their faith.

"After I covered, I changed," Rehan told me. "I felt I wanted to give people a good impression of Islam. I wanted people to know how happy I am to be Muslim." But not everyone understood, she said, recalling an incident in a supermarket in 2003: "The man next to me in the vegetable section said, 'You'd be much more beautiful without that thing on your head. It's demeaning to women.' " But to her the head scarf symbolized piety, not oppression.

A group of young college-educated women at the Dix mosque in Dearborn , Mich. , described the challenges many Muslims face as they carve out their identity in the United States . I spoke with them in the winter of 2004, after they had been to the mosque one Sunday for a halaqa (a study circle) focused on integrating faith and daily life. They were in their twenties: Hayat, a psychologist; Ismahan , a computer scientist; and Fatma , a third-grade teacher.

Hayat said veiling was easier for her than it had been for her sister,

10 years her senior, because Hayat had more Muslim peers when she reached high school and felt far less pressure to conform to American ways. When she went on to the University of Michigan , she was surrounded for the first time by young Muslims who dared to show pride in their religion in a non-Muslim setting.

Ismahan recalled similar experiences. In elementary school, she had tried to fit in. As an adult, though, "I know I don't have to fit in," she said. "I don't think Muslims have to assimilate. We are not treated like Americans . At work, I get up from my desk and go to pray. I thought I would face opposition from my boss. Even before I realized he didn't mind, I thought, 'I have a right to be a Muslim, and I don't have to assimilate.' "

Fatma described the mosque as central to her future: "What made me sane during years of public high school," she said, "was coming to the halaqa every Sunday." Fatma was also quick to distinguish herself from other young Muslim women who embrace American mores. "Some Muslims do anything to fit in. They drink. They date. My biggest fear is that I might assimilate to the American lifestyle so much that my modesty goes out the window."

Imam Zaid Shakir -- who teaches at San Francisco 's Zaytuna Institute, America 's only true madrassa -- refers to such young Muslims as the " rejectionist generation." They are rejectionist , he says, because they turn their backs not only on absolutist religious interpretations, but also on America 's secular ways. Many of these young American Muslims look to Shakir (and to celebrated Zaytuna founder Hamza Yusuf ) for guidance on how to live pious lives in the United States .

I spent several days at one of the institute's "mobile madrassas ," this one in San Jose , and watched hundreds of young Muslim professionals sit on cushioned folding chairs and listen intently as Yusuf delivered his lecture. "Everywhere I go, I see Muslims," he told them. "Go to the gas station and the airport. Muslims are present in the United States , and that was not true 20 years ago. There are more Muslims living outside the Dar al-Islam [Islamic countries, or literally the House of Islam] than ever. So we have to be strategic in our thinking, because people who are our enemies are strategic in their thinking."

The "enemies" Yusuf referred to that day were not non-Muslims, but rather those who use Islam as a rationale for violence. For the students at this madrassa and for many Muslims I interviewed, their strategy focuses on public displays of their faith.

Being ambassadors of Islam is daring behavior when you consider that American Muslims live in a country where so many people are ignorant of -- if not hostile to -- their faith. In a Gallup poll this year, when U.S. respondents were asked what they admire about the Muslim world, the most common response was "nothing" (33 percent); the second most common was "I don't know" (22 percent).

Despite contemporary public opinion -- or perhaps because of it -- Muslim Americans consider Islam their defining characteristic, beyond any national identity. In this way, their experience in the United States resembles that of their co-religionists in Europe , where mosques are also growing, Islamic schools are being built, and practicing the faith is the center of life, particularly for the young generation. In Europe and the United States, young Muslims are unifying around popular imams they believe understand the challenges they face in Western societies; these leaders include Yusuf in the United States and Amer Khaled, an Egyptian-born imam who lives in Britain. Thousands of young Muslims attend their lectures.

In my years of interviews, I found few indications of homegrown militancy among American Muslims. Indeed, thus far, they have proved they can compete economically with other Americans . Although the unemployment rate for Muslims in Britain is far higher than for most other groups, the average annual income of a Muslim household surpasses that of average American households. Yet, outside the workplace, Muslims retreat into the comfort zone of their mosques and Islamic schools.

It is too soon to say where the growing alienation of American Muslims will lead, but it seems clear that the factors contributing to it will endure. U.S. foreign policy persists in dividing Muslim and Western societies, making it harder still for Americans to realize that there is a difference between their Muslim neighbor and the plotter in London or the kidnapper in Baghdad .

geneive.abdo@geneiveabdo.com

Geneive Abdo is the liaison for the Alliance of Civilizations at the United Nations and author of " Mecca and Main Street : Muslim Life in America After 9/11" ( Oxford ).

Watandost means "friend of the nation or country". The blog contains news and views that are insightful but are often not part of the headlines. It also covers major debates in Muslim societies across the world including in the West. An earlier focus of the blog was on 'Pakistan and and its neighborhood' (2005 - 2017) the record of which is available in blog archive.

Thursday, August 31, 2006

Iran's Centrifuge Program: Defiant but Delayed:ISIS

Iran's Centrifuge Program: Defiant but Delayed

By David Albright and Jacqueline Shire

August 31, 2006: The Institute for Science and International Security (ISIS)

Despite Iran failing to meet U.S. Security Council demands to halt enrichment, progress at Natanz is slower than expected.

Iran has made limited progress at its Natanz uranium enrichment plant, installing and operating fewer gas centrifuges than expected. Senior Vienna-based diplomats have confirmed to ISIS that Iran may be either delaying deliberately the pace of its work while diplomatic efforts are underway, or is experiencing technical problems with its centrifuge program. It continues to conduct small experiments, and to operate a 164-machine cascade with uranium hexafluoride, but it is not operating this cascade consistently over a sustained period. ISIS has reported previously that Iran appears to be operating the cascade at reduced efficiency and output, yielding smaller quantities of low enriched uranium.

Iran has also failed to install as many cascades in the Natanz pilot plant as expected. In April 2006, U.S. government and IAEA officials expected Iran to have installed five cascades, each containing 164 centrifuges, by August 2006 at Natanz's pilot fuel enrichment plant (PFEP). (The PFEP is configured to hold a total of six cascades, but one "slot" holds five and ten machine cascades).

It now appears that Iran has not begun to operate the second and third cascades at the pilot plant, although they may be close to completion. There is no indication that Iran is close to installing the fourth and fifth cascades. To demonstrate proficiency in cascade operations, Iran must run these cascades together for an extended period of time.

Iran informed the IAEA of plans to begin installation of the first 3,000 centrifuges at Natanz's underground halls by the last quarter of 2006. It now appears that Iran will also not meet this deadline. It is possible that Iran's leadership has deferred installation out of concern that the facility would be a target of military strikes should diplomacy fail to resolve the nuclear issue. It is also possible that Iran has prepared undisclosed facilities for research and development of uranium centrifuges and deployment of additional cascades, although no evidence of such facilities currently operating has emerged from IAEA inspections.

By David Albright and Jacqueline Shire

August 31, 2006: The Institute for Science and International Security (ISIS)

Despite Iran failing to meet U.S. Security Council demands to halt enrichment, progress at Natanz is slower than expected.

Iran has made limited progress at its Natanz uranium enrichment plant, installing and operating fewer gas centrifuges than expected. Senior Vienna-based diplomats have confirmed to ISIS that Iran may be either delaying deliberately the pace of its work while diplomatic efforts are underway, or is experiencing technical problems with its centrifuge program. It continues to conduct small experiments, and to operate a 164-machine cascade with uranium hexafluoride, but it is not operating this cascade consistently over a sustained period. ISIS has reported previously that Iran appears to be operating the cascade at reduced efficiency and output, yielding smaller quantities of low enriched uranium.

Iran has also failed to install as many cascades in the Natanz pilot plant as expected. In April 2006, U.S. government and IAEA officials expected Iran to have installed five cascades, each containing 164 centrifuges, by August 2006 at Natanz's pilot fuel enrichment plant (PFEP). (The PFEP is configured to hold a total of six cascades, but one "slot" holds five and ten machine cascades).

It now appears that Iran has not begun to operate the second and third cascades at the pilot plant, although they may be close to completion. There is no indication that Iran is close to installing the fourth and fifth cascades. To demonstrate proficiency in cascade operations, Iran must run these cascades together for an extended period of time.

Iran informed the IAEA of plans to begin installation of the first 3,000 centrifuges at Natanz's underground halls by the last quarter of 2006. It now appears that Iran will also not meet this deadline. It is possible that Iran's leadership has deferred installation out of concern that the facility would be a target of military strikes should diplomacy fail to resolve the nuclear issue. It is also possible that Iran has prepared undisclosed facilities for research and development of uranium centrifuges and deployment of additional cascades, although no evidence of such facilities currently operating has emerged from IAEA inspections.

Wednesday, August 30, 2006

Pakistani intelligence services and their contributions!

Intelligence reports hurting careers of civilian bureaucrats

By Ansar Abbasi

The News, August 30, 2006

ISLAMABAD: Reports by intelligence agencies continue to cast a shadow over the careers of civilian bureaucrats, the latest evidence of which was provided by the recent high-powered promotion board meetings that recommended supersession/deferment of different officers, who slipped in the eyes of the spies.

Sources said that during its two days (Aug 28-29) consideration of high-level promotions, the Central Selection Board (CSB) superseded or deferred officers on the basis of intelligence reports.

In certain cases, where one or more members of the CSB on the basis of their personal knowledge challenged the credibility of the agencies' reports on officer(s), the board ignored the intelligence stories and recommended the concerned officers' elevation to higher grade.

In some cases, where there was division in the board about the authenticity of the intelligence report, the CSB recommended deferment of the concerned officers.

At the same time, the CSB sought fresh reports from intelligence agencies on the officers for consideration in the next board meeting.

A source said the board discussed the issue of intelligence reports, which, in many cases, are believed to be biased, subjective and not based on fact

Consequences of Bugti Murder: Ahmed Rashid's Analysis

Extracts from

Rebel killing raises stakes in Pakistan

Ahmed Rashid

BBC August 30, 2006

Senior politicians say that Mr Musharraf's lack of understanding about the Baloch issue, his underestimation of the growing sense of alienation in all the smaller provinces and the attack on his ego when his helicopter was fired upon by Baloch rebels last December, all contributed to his helping him take the decision to kill Bugti.

The army argues that millions have been spent in development, but projects such as the building of the Gawadar port, the building of cantonments and even new roads do not necessarily benefit ordinary Baloch.

The projects are defined by the army and its national security needs, rather than through consultations with the Baloch or even the Balochistan provincial assembly. Then the projects are carried out by outside companies who give few jobs to the Baloch.

There is an ever-deepening political crisis in Pakistan which the death of Bugti will only exacerbate.

Many people say that the country is rapidly unravelling with Mr Musharraf refusing to give clear-cut guarantees about free and fair elections next year, while he insists on running again for another five-year term as president even as he remains army chief.

For complete article, click here

Future of Pakistan?

Extracts from

WASHINGTON DIARY: A murder foretold? —Dr Manzur Ejaz

Daily Times, August 30, 2006

We were sharing the experiences of an expert from an international organisation who has recently visited Pakistan and some areas of Afghanistan. When someone broke the news of Nawab Akbar Bugti’s killing, it seemed to be part of his presentation to be fully revealed to the audience after a prologue. As if it was to prove his point that Pakistan’s map may go through changes in the not-too-distant future.

He disclosed that he had been to several seminars where international speakers mentioned Balochistan and the North West Frontier Province (NWFP) as part of Central Asia and Sindh and Punjab as part of Indian civilisation. He was asked about a recent article by Peter Ralph that discussed new alignments in the region, however he had not heard about it, and emphasised that he was not referring to a single person or a single seminar but an emerging pattern of thinking which indicated that, sooner or later, the civilisation factor will assert and redraw the map of Pakistan.

He was not very optimistic about the union of Sindh and Punjab either. The pace and patterns of development were so divergent and disparate, he said, that ultimately the gulf between two provinces would widen. Because of better management and in the absence of ethnic contradictions Punjab was growing much faster while rampant corruption, incompetence and inaction held Sindh back. The province was completely paralysed. And irrespective of whether Punjab capitalises on its indigenous resources or outside help, Sindhis on Lahore’s roads are going to smell their blood and sweat.

Unlike the past years he was very appreciative of the present institutional set-up in the Punjab. All international institutions and their experts, he informed us, wanted to work with the Punjab and lend it money. Most of the consultants and experts from international organisation preferred to stay in Lahore and work from there. Being assigned to a project in Sindh or Balochistan was considered a punishment. In his view, this was due to visible changes in government functioning and getting the visible results that every project manager is appraised for.

For complete article clic here

WASHINGTON DIARY: A murder foretold? —Dr Manzur Ejaz

Daily Times, August 30, 2006

We were sharing the experiences of an expert from an international organisation who has recently visited Pakistan and some areas of Afghanistan. When someone broke the news of Nawab Akbar Bugti’s killing, it seemed to be part of his presentation to be fully revealed to the audience after a prologue. As if it was to prove his point that Pakistan’s map may go through changes in the not-too-distant future.

He disclosed that he had been to several seminars where international speakers mentioned Balochistan and the North West Frontier Province (NWFP) as part of Central Asia and Sindh and Punjab as part of Indian civilisation. He was asked about a recent article by Peter Ralph that discussed new alignments in the region, however he had not heard about it, and emphasised that he was not referring to a single person or a single seminar but an emerging pattern of thinking which indicated that, sooner or later, the civilisation factor will assert and redraw the map of Pakistan.

He was not very optimistic about the union of Sindh and Punjab either. The pace and patterns of development were so divergent and disparate, he said, that ultimately the gulf between two provinces would widen. Because of better management and in the absence of ethnic contradictions Punjab was growing much faster while rampant corruption, incompetence and inaction held Sindh back. The province was completely paralysed. And irrespective of whether Punjab capitalises on its indigenous resources or outside help, Sindhis on Lahore’s roads are going to smell their blood and sweat.

Unlike the past years he was very appreciative of the present institutional set-up in the Punjab. All international institutions and their experts, he informed us, wanted to work with the Punjab and lend it money. Most of the consultants and experts from international organisation preferred to stay in Lahore and work from there. Being assigned to a project in Sindh or Balochistan was considered a punishment. In his view, this was due to visible changes in government functioning and getting the visible results that every project manager is appraised for.

For complete article clic here

Tuesday, August 29, 2006

A Patriotic Act

Nasim Zehra's Statement Declining Acceptance of Sitara-i-Imtiaz

To protest the dreadful act of the killing of a Pakistani political leader Sardar Akbar Bugti by Pakistan's security forces, I decline to accept the Sitara-i-Imtiaz for which I was nominated by the President of Pakistan on August 14. It is with deep personal regret that I take this decision since national awards are a symbol of honor and a matter of immense pride and gratitude. At this juncture protesting the State's proclivity to opt for use of force to settle complex political problems, must take precedence over matters of personal consideration.

Unfortunately in the latest round of a two year long Baluchistan-Centre crisis those elements finally won on August 26 who all along believed that force was the way to settling the current crisis. The militaristic elements trumped those within the system who were pushing for a political resolution through the Parliamentary Committee on Baluchistan.

Clearly our foremost task in Pakistan is to strengthen civilian political forces which believe in the rule of law and understand the need to resolve Pakistan's internal problems through consensus and reconciliation. In ignoring these principles we have committed three cardinal blunders. First alienation of East Pakistanis leading to the tragic breakup of Pakistan , the judicial murder of an elected Prime

Minister and now the killing of another prominent political leader. We must make every effort to institute the required checks and balances in the exercize of power that would avoid repeat of such blunders.

To protest the dreadful act of the killing of a Pakistani political leader Sardar Akbar Bugti by Pakistan's security forces, I decline to accept the Sitara-i-Imtiaz for which I was nominated by the President of Pakistan on August 14. It is with deep personal regret that I take this decision since national awards are a symbol of honor and a matter of immense pride and gratitude. At this juncture protesting the State's proclivity to opt for use of force to settle complex political problems, must take precedence over matters of personal consideration.

Unfortunately in the latest round of a two year long Baluchistan-Centre crisis those elements finally won on August 26 who all along believed that force was the way to settling the current crisis. The militaristic elements trumped those within the system who were pushing for a political resolution through the Parliamentary Committee on Baluchistan.

Clearly our foremost task in Pakistan is to strengthen civilian political forces which believe in the rule of law and understand the need to resolve Pakistan's internal problems through consensus and reconciliation. In ignoring these principles we have committed three cardinal blunders. First alienation of East Pakistanis leading to the tragic breakup of Pakistan , the judicial murder of an elected Prime

Minister and now the killing of another prominent political leader. We must make every effort to institute the required checks and balances in the exercize of power that would avoid repeat of such blunders.

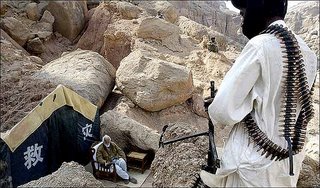

Fiction from the Frontlines of War on Terror

Fiction from the Frontlines

Newsline, August 2006

Journalists cashed in on the demand for sensational stories during the US-led war in Afghanistan by interviewing fake Taliban and Al Qaeda members and quoting "anonymous" sources.

By Amir Zia

Islamabad 2001: A Pakistani journalist was urging a retired army officer on telephone to pose as a serving Inter-Services Intelligence official and give an interview to the bureau chief of a leading western wire agency as an anonymous source. After arguing with the retired official for several minutes in a mix of Urdu and Punjabi, the journalist finally called out to his bureau chief saying that his ISI source was on the line.

An hour after the telephone interview, the western agency filed a sensational story about the divide within the ranks of Pakistan's military establishment and ISI's opposition to President Pervez Musharraf's decision to withdraw support to the Afghan Taliban.

The story was a hit - and so was the stringer who arranged the fake interview.

As hundreds of foreign correspondents descended on Islamabad, Peshawar, Quetta, and some, even Karachi, to report on the war in Afghanistan and terrorism, a new breed of journalists, known usually as "fixers," and stringers, got unprecedented importance.

The majority of foreign journalists were unable to go inside Afghanistan to cover the war and were desperately trying instead, to find some exciting stories from within Pakistan. Small pro-Taliban rallies were being blown out of proportion and many Pakistani stringers were aiding them in procuring quotes from "anonymous" army, intelligence and interior ministry officials to support their pre-conceived stories about Pakistan and its role in terrorism.

In addition, "fake" interviews with the Taliban and Islamic militants were also conducted.

The task of genuine journalists, who wanted to file only factual stories, was becoming increasingly difficult because they were competing against these sensationalist stories.

Often reputed foreign newspapers and wire agencies ran stories without verifying them because of stiff competition.

International wire agencies, which usually avoid anonymous sources as a rule of thumb, lowered their standards of proper sourcing, banking more and more on mysterious anonymous sources, from places like Multan, Lahore and Peshawar, which often fed them detailed accounts of the interrogation of some key Al Qaeda suspect being conducted in Islamabad.

Often the same story had different versions; at other times, stringers lifted the content from the story of a rival agency/newspaper and peppered it with their own language to make it sound different.

The real irony was, despite the fact that foreign media organisations would often recognise that the information was not credible, they still went ahead and used it. In fact, some of these international wire services and newspapers actually sought out stringers who claimed that they had close contacts with intelligence agencies and paid them handsomely for their "work."

A reputed foreign newspaper filed a story regarding the defection of Afghan foreign minister, Abdul Wakil Muttawakil, which proved to be totally incorrect, much to the editor's embarrassment.

Often, intelligence officials exchanged information with some journalists on a quid-pro-quo basis and used them to leak information and even plant misleading stories.

Then there were many Afghans, who were desperately trying to sell all sorts of stories about Al Qaeda camps and the Afghan Taliban to western journalists in exchange for a few bucks. One such Afghan stringer claimed that he had escaped from the Kandahar prison of the Taliban/Al Qaeda, but later it was discovered that he had been living at an Afghan refugee camp in Peshawar for the past one year.

Some daring local journalist even presented Pakistani tribesmen as fierce Afghan Taliban warriors.

French correspondent Joel Marc Epstein and photographer Jean Paul Guilloteau of the Paris weekly L'Express, and their local stringer Khawar Rizvi, were arrested in Balochistan in December 2003 on charges of arranging interviews and photographs of "fake Taliban."

The trend of concocting stories and quoting fake anonymous sources that started during the time of the U.S.-led war on terrorism, continues to this day. And what's more, it has helped change the fortunes of dozens of stringers who earned mega-bucks in dollars for their dubious "meritorious" services.

Newsline, August 2006

Journalists cashed in on the demand for sensational stories during the US-led war in Afghanistan by interviewing fake Taliban and Al Qaeda members and quoting "anonymous" sources.

By Amir Zia

Islamabad 2001: A Pakistani journalist was urging a retired army officer on telephone to pose as a serving Inter-Services Intelligence official and give an interview to the bureau chief of a leading western wire agency as an anonymous source. After arguing with the retired official for several minutes in a mix of Urdu and Punjabi, the journalist finally called out to his bureau chief saying that his ISI source was on the line.

An hour after the telephone interview, the western agency filed a sensational story about the divide within the ranks of Pakistan's military establishment and ISI's opposition to President Pervez Musharraf's decision to withdraw support to the Afghan Taliban.

The story was a hit - and so was the stringer who arranged the fake interview.

As hundreds of foreign correspondents descended on Islamabad, Peshawar, Quetta, and some, even Karachi, to report on the war in Afghanistan and terrorism, a new breed of journalists, known usually as "fixers," and stringers, got unprecedented importance.

The majority of foreign journalists were unable to go inside Afghanistan to cover the war and were desperately trying instead, to find some exciting stories from within Pakistan. Small pro-Taliban rallies were being blown out of proportion and many Pakistani stringers were aiding them in procuring quotes from "anonymous" army, intelligence and interior ministry officials to support their pre-conceived stories about Pakistan and its role in terrorism.

In addition, "fake" interviews with the Taliban and Islamic militants were also conducted.

The task of genuine journalists, who wanted to file only factual stories, was becoming increasingly difficult because they were competing against these sensationalist stories.

Often reputed foreign newspapers and wire agencies ran stories without verifying them because of stiff competition.

International wire agencies, which usually avoid anonymous sources as a rule of thumb, lowered their standards of proper sourcing, banking more and more on mysterious anonymous sources, from places like Multan, Lahore and Peshawar, which often fed them detailed accounts of the interrogation of some key Al Qaeda suspect being conducted in Islamabad.

Often the same story had different versions; at other times, stringers lifted the content from the story of a rival agency/newspaper and peppered it with their own language to make it sound different.

The real irony was, despite the fact that foreign media organisations would often recognise that the information was not credible, they still went ahead and used it. In fact, some of these international wire services and newspapers actually sought out stringers who claimed that they had close contacts with intelligence agencies and paid them handsomely for their "work."

A reputed foreign newspaper filed a story regarding the defection of Afghan foreign minister, Abdul Wakil Muttawakil, which proved to be totally incorrect, much to the editor's embarrassment.

Often, intelligence officials exchanged information with some journalists on a quid-pro-quo basis and used them to leak information and even plant misleading stories.

Then there were many Afghans, who were desperately trying to sell all sorts of stories about Al Qaeda camps and the Afghan Taliban to western journalists in exchange for a few bucks. One such Afghan stringer claimed that he had escaped from the Kandahar prison of the Taliban/Al Qaeda, but later it was discovered that he had been living at an Afghan refugee camp in Peshawar for the past one year.

Some daring local journalist even presented Pakistani tribesmen as fierce Afghan Taliban warriors.

French correspondent Joel Marc Epstein and photographer Jean Paul Guilloteau of the Paris weekly L'Express, and their local stringer Khawar Rizvi, were arrested in Balochistan in December 2003 on charges of arranging interviews and photographs of "fake Taliban."

The trend of concocting stories and quoting fake anonymous sources that started during the time of the U.S.-led war on terrorism, continues to this day. And what's more, it has helped change the fortunes of dozens of stringers who earned mega-bucks in dollars for their dubious "meritorious" services.

Monday, August 28, 2006

Gen. Abiaid should inform his hosts how the US military is subserviant to its democratic leadership

Picture source: www.centcom.mil

Pakistan, US to improve military cooperation

Online: August 29, 2006

RAWALPINDI: Pakistan and the US decided on Monday to take defence and military cooperation to another level.

The decision was made at a meeting between General John P Abizaid, commander of the US Central Command, and Vice Chief of Army Staff General Ahsan Saleem Hayat. Sources said that both sides had agreed to bolster defence relations. Gen Abizaid held out his assurance that the US would train the Pakistani military. He acknowledged Pakistan’s role in the war on terror. Gen Abizaid will meet President General Pervez Musharraf today (Tuesday). online

India and Pakistan palying their Great Game in Baluchistan

India, Pakistan playing their ‘Great Game’

Josy Joseph

Daily News and Analysis; August 28, 2006

A DNA Analysis

NEW DELHI: For long, Pakistan has accused India of fuelling rebellion in Baluchistan. India has vehemently denied any involvement, though it has in recent past and on Monday made statements against Pakistan’s suppression of the rebels.

Pakistan accuses India of using its missions in Afghanistan to train Baluch rebels and arming them. India has reasons to fuel trouble in Pakistan’s biggest province: in the short-run it would keep Pakistan engaged and troubled, and would stymie its ability to focus further on Kashmir. It looks perfectly like the South Asian dog-eat-dog world of counter-intelligence and covert operations.

There has never been any credible evidence to prove Pakistan’s claims, but there is no reason to believe Indian agencies are not interested in Baluch rebels. It is a fact that India for long has been closely watching the situation in Baluchistan due to its strategic location. Not just Pakistan’s richest region in terms of natural resources, the tribal land is also where many of Pakistan’s strategic assets are located. Trouble there should be gladdening to majority in the Indian strategic community who are steeped in the Partition mindset.

A troubled Baluchistan, which it is presently, would be of serious concern to Pakistan. That is where its biggest port project is underway. The Gwadar port, being built with Chinese assistance, would not just be Pakistan’s biggest seaport but also its most important location for naval assets in future. Gwadar is on the southwestern coast of Pakistan, next door to the Strait of Hormuz, a major sea-lane for oil and other cargo. Chagai Hills, where Pakistan conducted the 1998 nuclear tests, is in north-western Baluchistan.

The killing of Nawab Akbar Khan Bugti could have serious long-term repercussions not just in Baluchistan but across South Asia. In Baluch a new martyr is born. Across South Asia, the tremors of a possible redrawing of national boundaries can be felt again. The possibility of Baluchistan disintegrating are distant, but it cannot be ruled out. Given its strategic location and interest of various groups including the Americans in Baluchistan only adds to the possibility of the rebellion remaining robust into the future.

Also see, Bugti: The Making of a Martyr by Imtiaz Alam in The News

Reuters' Key Facts on Baluchistan

"Kashmir on the Thames": British - Pakistanis in Focus

Kashmir on the Thames: London Broil

by Peter Bergen & Paul Cruickshank

August 25, 2006: The New Republic

London, England

In New Year's Eve in 1999, Islamist militants had plenty to celebrate. At the Taliban-controlled Kandahar airport, a planeload of hostages was being swapped for terrorists held in India. The hijackers--Kashmiri militants--had managed to secure the freedom of three key allies. Two, Maulana Masood Azhar and Mushtaq Ahmed Zargar, were Pakistani; but the third, a man named Omar Sheikh, was the scion of a wealthy British Pakistani family and had studied at the London School of Economics.

That a British citizen figured so prominently in the Kandahar hostage crisis was disturbing but far from anomalous. The eleven people charged this week with conspiring to blow up planes using liquid explosives are all British citizens. So were the terrorists who attacked London in 2005, almost all of the plotters who allegedly conspired to detonate a fertilizer bomb in England in 2004, the suicide bombers who attacked a beachfront Tel Aviv bar in 2003, and an alleged Al Qaeda operative who, along with would-be shoe bomber Richard Reid, planned to explode a plane in the fall of 2001.

Besides holding British citizenship, most had one other thing in common with Omar Sheikh: They were of Pakistani descent. For terrorist organizations like Al Qaeda--which, in the years since American troops deposed the Taliban, has reconstituted itself in Pakistan--ethnic Pakistanis living in the United Kingdom make perfect recruits, since they speak English and can travel on British passports. Indeed, in the wake of this month's high-profile arrests, it can now be argued that the biggest threat to U.S. security emanates not from Iran or Iraq or Afghanistan--but rather from Great Britain, our closest ally.

necdotal evidence for the influence of Muslim extremism on British Pakistani communities is not hard to come by. We visited the Al Badr Health & Fitness Centre in East London on a balmy June night to hear Abu Muwaheed--a leader of the Saviour Sect, an Islamist group--discuss who was to blame for the 2005 London bombings. His answer? Just about everyone but the bombers themselves--the British government, the British public, even moderate Muslims who betrayed their co-religionists by cooperating with the government. The evening included a video montage of fighting in Iraq that ended with footage of Osama bin Laden calling for jihad. One Pakistani man attending the session told us he considered the lead suicide bomber in the London attacks to be "a glorious martyr." Two months later, five of the Fitness Centre's regulars would be among those arrested in connection with the plot to bomb transatlantic flights.

How did Al Qaeda's militant worldview become so popular among a subset of British Pakistanis? For one thing, there is the generational divide in the community. Just as in Turgenev's Fathers and Sons--which depicts the rift between an older generation of nineteenth-century Russian liberals and their more militant, socialist sons--some of Great Britain's young Pakistanis are filled with contempt both for the moderation of their parents and for a British society that won't quite accept them. For many, this leaves a vacuum in their identities that radical Islamist preachers have been all too glad to fill. Now, young disciples of those preachers--Abu Muwaheed, for instance--have come into their own, and they are often even more radical than their mentors. Add to this the fact that one-quarter of young British Pakistanis are unemployed, and you have a population that is especially vulnerable to the temptations of radicalism.

Still, homegrown militancy can only partly account for the problem. That's because it is primarily in Pakistan--not the United Kingdom--where British citizens are being recruited into Al Qaeda and other terrorist groups. About 400,000 British Pakistanis per year travel back to their homeland, where a small percentage embark on learning the skills necessary to become effective terrorists. Several of the British citizens recently suspected of plotting to blow up airliners reportedly went to Pakistan to meet Al Qaeda operatives. According to a government report released this year, British officials believe that the lead perpetrators of the 2005 attacks in London--Mohammed Siddique Khan and Shehzad Tanweer--met with Al Qaeda members in Pakistan. Several individuals allegedly involved in a 2004 plot to explode a fertilizer bomb in Great Britain also spent significant time in Pakistan. In April 2003, Omar Khan Sharif, whose family immigrated to Great Britain from Kashmir, attempted to carry out a suicide attack in a bar in Tel Aviv after visiting Pakistan. In 2001, according to British prosecutors, he e-mailed his wife from there, writing, "We will definitely, inshallah, meet soon, if not in this life then the next." And, in the fall of 2001, Sajit Badat plotted to explode a transatlantic airliner with a shoe bomb shortly after spending time in a Pakistani training camp.

But how to explain the lure of militancy for those who travel to Pakistan to become terrorists? The answer, in many cases, is Kashmir. A disproportionate number of Pakistanis living in Great Britain trace their lineage back to Kashmir. Though conventional wisdom holds that anger toward U.S. foreign policy is most responsible for creating new terrorists, among British Pakistanis, Kashmir is probably just as important. What's more, for the small number of British Pakistanis who want terrorist training, the facilities of Kashmiri militant groups have become an obvious first choice--as well as a gateway to Al Qaeda itself.

Al Qaeda's ties with Kashmiri militant groups date to the Afghan war against the Soviets, when bin Laden's forces fought alongside Pakistani groups like Lashkar-e-Toiba (LeT). After the Soviet withdrawal from Afghanistan, many of those groups turned their attention to Kashmir--the key reason why the Kashmiri conflict re-erupted in the 1990s. These ties endured throughout the decade and grew closer after Al Qaeda left Sudan and settled in Afghanistan in 1996. President Clinton's August 1998 cruise-missile strike against an Al Qaeda base in eastern Afghanistan killed a number of members of Harakat Ul Mujihadeen, one of the largest Kashmiri militant groups--suggesting that it was sharing training facilities with Al Qaeda.

Since September 11, the relationship between Al Qaeda and Kashmiri groups has only deepened, as demonstrated by the fact that Al Qaeda operative Abu Zubaydah was arrested in an LeT safehouse in Pakistan in 2002. Al Qaeda has been able to regroup in Pakistan after losing its base in Afghanistan in part by cooperating with Kashmiri militants. A senior American military intelligence official told us that there is "no difference" between Al Qaeda and Kashmiri terrorist organizations. Al Qaeda has also attempted to fit the Kashmir dispute into its anti-American narrative: Hamid Mir, a Pakistani journalist who is writing bin Laden's authorized biography, told us that Al Qaeda propaganda accuses Pakistan's government of selling out Kashmir under pressure from George Bush and Tony Blair.

The danger to the United States of the nexus between British Pakistanis, Al Qaeda, and Kashmir is becoming clear. One of the alleged ringleaders of the recently exposed plot to blow up transatlantic flights is Rashid Rauf, a Pakistan-born British citizen whose family immigrated to Great Britain from Kashmir. According to the Associated Press, Rauf is married to a sister-in-law of Maulana Masood Azhar, the leader of the Kashmiri terrorist group Jaish-e-Mohammed (and one of the men released as part of the deal that ended the Kandahar hostage standoff in 1999). Previously, in 2004, British authorities had charged eight men--many of Pakistani descent--with planning terrorism, including a plot to blow up the New York Stock Exchange. The cell's alleged leader, Abu Issa Al Hindi, a British convert to Islam, wrote a book explaining how he was radicalized by his experience fighting in Kashmir. In March 2006, British citizen Mohammed Ajmal Khan was sentenced to nine years for fund-raising on behalf of terrorism in Pakistan and Afghanistan. Khan admitted attending a terrorist training camp run by LeT. The judge in Khan's case described him as "a terrorist quartermaster" for LeT. According to The Daily Telegraph, he was a frequent visitor to the United States and talked about attacking U.S. synagogues. American prosecutors say Khan was in touch with a group of Virginia militants also tied to LeT.

ll of this should raise two concerns for American officials. The first is that American Pakistanis could pose a similar threat. "Homegrown terrorists may prove to be as dangerous as groups like Al Qaeda, if not more so," FBI Director Robert Mueller warned in June. There are reasons to worry that he is right. Two and a half months ago, an FBI affidavit contends, Syed Haris Ahmed, an American citizen of Pakistani descent, traveled from Atlanta to Ontario to meet with a terrorist cell. The FBI alleges that Ahmed, now in U.S. custody, planned to attend a terrorist training camp in Pakistan. In 2003, Iyman Faris, an American citizen born in Kashmir, pleaded guilty to helping Al Qaeda plan attacks in the United States. Faris admitted to meeting Khalid Sheikh Mohammed--the mastermind of the September 11 attacks--in Pakistan to plan those operations in 2002.

Yet it seems unlikely that radicalism in the American Pakistani community could pose as large a threat as radicalism in the British Pakistani community. American Muslims are, on average, more politically moderate than their British counterparts. According to a 2001 survey, 70 percent of American Muslims strongly agreed that they should participate in U.S. institutions. By contrast, a recent Pew poll found that 81 percent of British Muslims considered themselves Muslims first and British citizens second.

Of more concern, then, is the likelihood that British Pakistanis will continue to target Americans--both in the United States and abroad. To address this problem, the Bush administration should encourage the British government to monitor more closely the activities of U.K.-based extremist groups. Simply banning these organizations is not enough. Weeks after we attended one of their meetings, the Saviour Sect was outlawed by British Home Secretary John Reid. But, when we spoke to one of the organization's leaders, Anjem Choudhary, by phone, he told us, "Of course we don't use that name anymore. We just hold our meetings under another name." In addition, Great Britain must step up efforts to identify its own citizens who attend Kashmiri or Al Qaeda training camps in Pakistan.

Unfortunately, there are limits to what the British government can do alone. It will need help from moderate Muslims, some of whom are waking up to the threat posed by the radicals in their midst. "These people are ill," says Ghulam Rabbani, the imam of the mosque adjoining the Fitness Centre, where the Saviour Sect held meetings. "I say very categorically and very clearly that they are misguided and they don't know the basics of Islam."

Rabbani faces a steep challenge: According to a recent poll, a full quarter of British Muslims consider the 2005 London bombings justified. And anyone who doubts how dangerous the intersection of such sentiments, Al Qaeda, and Kashmiri militants can be should consider what became of Omar Sheikh, the former London School of Economics student who won his freedom on New Year's Eve in 1999: Two years later, he was under arrest for orchestrating the murder of Wall Street Journal reporter Daniel Pearl.

Peter Bergen is a senior fellow at the New American Foundation and the author of The Osama bin Laden I Know. Paul Cruickshank is a fellow at New York University Law School's Center on Law and Security.

by Peter Bergen & Paul Cruickshank

August 25, 2006: The New Republic

London, England

In New Year's Eve in 1999, Islamist militants had plenty to celebrate. At the Taliban-controlled Kandahar airport, a planeload of hostages was being swapped for terrorists held in India. The hijackers--Kashmiri militants--had managed to secure the freedom of three key allies. Two, Maulana Masood Azhar and Mushtaq Ahmed Zargar, were Pakistani; but the third, a man named Omar Sheikh, was the scion of a wealthy British Pakistani family and had studied at the London School of Economics.

That a British citizen figured so prominently in the Kandahar hostage crisis was disturbing but far from anomalous. The eleven people charged this week with conspiring to blow up planes using liquid explosives are all British citizens. So were the terrorists who attacked London in 2005, almost all of the plotters who allegedly conspired to detonate a fertilizer bomb in England in 2004, the suicide bombers who attacked a beachfront Tel Aviv bar in 2003, and an alleged Al Qaeda operative who, along with would-be shoe bomber Richard Reid, planned to explode a plane in the fall of 2001.

Besides holding British citizenship, most had one other thing in common with Omar Sheikh: They were of Pakistani descent. For terrorist organizations like Al Qaeda--which, in the years since American troops deposed the Taliban, has reconstituted itself in Pakistan--ethnic Pakistanis living in the United Kingdom make perfect recruits, since they speak English and can travel on British passports. Indeed, in the wake of this month's high-profile arrests, it can now be argued that the biggest threat to U.S. security emanates not from Iran or Iraq or Afghanistan--but rather from Great Britain, our closest ally.

necdotal evidence for the influence of Muslim extremism on British Pakistani communities is not hard to come by. We visited the Al Badr Health & Fitness Centre in East London on a balmy June night to hear Abu Muwaheed--a leader of the Saviour Sect, an Islamist group--discuss who was to blame for the 2005 London bombings. His answer? Just about everyone but the bombers themselves--the British government, the British public, even moderate Muslims who betrayed their co-religionists by cooperating with the government. The evening included a video montage of fighting in Iraq that ended with footage of Osama bin Laden calling for jihad. One Pakistani man attending the session told us he considered the lead suicide bomber in the London attacks to be "a glorious martyr." Two months later, five of the Fitness Centre's regulars would be among those arrested in connection with the plot to bomb transatlantic flights.

How did Al Qaeda's militant worldview become so popular among a subset of British Pakistanis? For one thing, there is the generational divide in the community. Just as in Turgenev's Fathers and Sons--which depicts the rift between an older generation of nineteenth-century Russian liberals and their more militant, socialist sons--some of Great Britain's young Pakistanis are filled with contempt both for the moderation of their parents and for a British society that won't quite accept them. For many, this leaves a vacuum in their identities that radical Islamist preachers have been all too glad to fill. Now, young disciples of those preachers--Abu Muwaheed, for instance--have come into their own, and they are often even more radical than their mentors. Add to this the fact that one-quarter of young British Pakistanis are unemployed, and you have a population that is especially vulnerable to the temptations of radicalism.

Still, homegrown militancy can only partly account for the problem. That's because it is primarily in Pakistan--not the United Kingdom--where British citizens are being recruited into Al Qaeda and other terrorist groups. About 400,000 British Pakistanis per year travel back to their homeland, where a small percentage embark on learning the skills necessary to become effective terrorists. Several of the British citizens recently suspected of plotting to blow up airliners reportedly went to Pakistan to meet Al Qaeda operatives. According to a government report released this year, British officials believe that the lead perpetrators of the 2005 attacks in London--Mohammed Siddique Khan and Shehzad Tanweer--met with Al Qaeda members in Pakistan. Several individuals allegedly involved in a 2004 plot to explode a fertilizer bomb in Great Britain also spent significant time in Pakistan. In April 2003, Omar Khan Sharif, whose family immigrated to Great Britain from Kashmir, attempted to carry out a suicide attack in a bar in Tel Aviv after visiting Pakistan. In 2001, according to British prosecutors, he e-mailed his wife from there, writing, "We will definitely, inshallah, meet soon, if not in this life then the next." And, in the fall of 2001, Sajit Badat plotted to explode a transatlantic airliner with a shoe bomb shortly after spending time in a Pakistani training camp.

But how to explain the lure of militancy for those who travel to Pakistan to become terrorists? The answer, in many cases, is Kashmir. A disproportionate number of Pakistanis living in Great Britain trace their lineage back to Kashmir. Though conventional wisdom holds that anger toward U.S. foreign policy is most responsible for creating new terrorists, among British Pakistanis, Kashmir is probably just as important. What's more, for the small number of British Pakistanis who want terrorist training, the facilities of Kashmiri militant groups have become an obvious first choice--as well as a gateway to Al Qaeda itself.

Al Qaeda's ties with Kashmiri militant groups date to the Afghan war against the Soviets, when bin Laden's forces fought alongside Pakistani groups like Lashkar-e-Toiba (LeT). After the Soviet withdrawal from Afghanistan, many of those groups turned their attention to Kashmir--the key reason why the Kashmiri conflict re-erupted in the 1990s. These ties endured throughout the decade and grew closer after Al Qaeda left Sudan and settled in Afghanistan in 1996. President Clinton's August 1998 cruise-missile strike against an Al Qaeda base in eastern Afghanistan killed a number of members of Harakat Ul Mujihadeen, one of the largest Kashmiri militant groups--suggesting that it was sharing training facilities with Al Qaeda.

Since September 11, the relationship between Al Qaeda and Kashmiri groups has only deepened, as demonstrated by the fact that Al Qaeda operative Abu Zubaydah was arrested in an LeT safehouse in Pakistan in 2002. Al Qaeda has been able to regroup in Pakistan after losing its base in Afghanistan in part by cooperating with Kashmiri militants. A senior American military intelligence official told us that there is "no difference" between Al Qaeda and Kashmiri terrorist organizations. Al Qaeda has also attempted to fit the Kashmir dispute into its anti-American narrative: Hamid Mir, a Pakistani journalist who is writing bin Laden's authorized biography, told us that Al Qaeda propaganda accuses Pakistan's government of selling out Kashmir under pressure from George Bush and Tony Blair.

The danger to the United States of the nexus between British Pakistanis, Al Qaeda, and Kashmir is becoming clear. One of the alleged ringleaders of the recently exposed plot to blow up transatlantic flights is Rashid Rauf, a Pakistan-born British citizen whose family immigrated to Great Britain from Kashmir. According to the Associated Press, Rauf is married to a sister-in-law of Maulana Masood Azhar, the leader of the Kashmiri terrorist group Jaish-e-Mohammed (and one of the men released as part of the deal that ended the Kandahar hostage standoff in 1999). Previously, in 2004, British authorities had charged eight men--many of Pakistani descent--with planning terrorism, including a plot to blow up the New York Stock Exchange. The cell's alleged leader, Abu Issa Al Hindi, a British convert to Islam, wrote a book explaining how he was radicalized by his experience fighting in Kashmir. In March 2006, British citizen Mohammed Ajmal Khan was sentenced to nine years for fund-raising on behalf of terrorism in Pakistan and Afghanistan. Khan admitted attending a terrorist training camp run by LeT. The judge in Khan's case described him as "a terrorist quartermaster" for LeT. According to The Daily Telegraph, he was a frequent visitor to the United States and talked about attacking U.S. synagogues. American prosecutors say Khan was in touch with a group of Virginia militants also tied to LeT.

ll of this should raise two concerns for American officials. The first is that American Pakistanis could pose a similar threat. "Homegrown terrorists may prove to be as dangerous as groups like Al Qaeda, if not more so," FBI Director Robert Mueller warned in June. There are reasons to worry that he is right. Two and a half months ago, an FBI affidavit contends, Syed Haris Ahmed, an American citizen of Pakistani descent, traveled from Atlanta to Ontario to meet with a terrorist cell. The FBI alleges that Ahmed, now in U.S. custody, planned to attend a terrorist training camp in Pakistan. In 2003, Iyman Faris, an American citizen born in Kashmir, pleaded guilty to helping Al Qaeda plan attacks in the United States. Faris admitted to meeting Khalid Sheikh Mohammed--the mastermind of the September 11 attacks--in Pakistan to plan those operations in 2002.

Yet it seems unlikely that radicalism in the American Pakistani community could pose as large a threat as radicalism in the British Pakistani community. American Muslims are, on average, more politically moderate than their British counterparts. According to a 2001 survey, 70 percent of American Muslims strongly agreed that they should participate in U.S. institutions. By contrast, a recent Pew poll found that 81 percent of British Muslims considered themselves Muslims first and British citizens second.

Of more concern, then, is the likelihood that British Pakistanis will continue to target Americans--both in the United States and abroad. To address this problem, the Bush administration should encourage the British government to monitor more closely the activities of U.K.-based extremist groups. Simply banning these organizations is not enough. Weeks after we attended one of their meetings, the Saviour Sect was outlawed by British Home Secretary John Reid. But, when we spoke to one of the organization's leaders, Anjem Choudhary, by phone, he told us, "Of course we don't use that name anymore. We just hold our meetings under another name." In addition, Great Britain must step up efforts to identify its own citizens who attend Kashmiri or Al Qaeda training camps in Pakistan.

Unfortunately, there are limits to what the British government can do alone. It will need help from moderate Muslims, some of whom are waking up to the threat posed by the radicals in their midst. "These people are ill," says Ghulam Rabbani, the imam of the mosque adjoining the Fitness Centre, where the Saviour Sect held meetings. "I say very categorically and very clearly that they are misguided and they don't know the basics of Islam."

Rabbani faces a steep challenge: According to a recent poll, a full quarter of British Muslims consider the 2005 London bombings justified. And anyone who doubts how dangerous the intersection of such sentiments, Al Qaeda, and Kashmiri militants can be should consider what became of Omar Sheikh, the former London School of Economics student who won his freedom on New Year's Eve in 1999: Two years later, he was under arrest for orchestrating the murder of Wall Street Journal reporter Daniel Pearl.

Peter Bergen is a senior fellow at the New American Foundation and the author of The Osama bin Laden I Know. Paul Cruickshank is a fellow at New York University Law School's Center on Law and Security.

Sunday, August 27, 2006

"Bugti’s killing is the biggest blunder since Bhutto’s execution"

Extracts from Daily Times Editorial: August 29, 2006

Whoever in the national security establishment decided to eliminate Nawab Bugti physically is clueless about the force of politics, history and nationalism. Clearly, this was a politically inopportune moment for it. Most of what the opposition will say about the killing of Mr Bugti is going to gibe with what leading PMLQ politicians have felt: that the deadlock in Balochistan should not be resolved through military action. The ruling party is already bedevilled with rifts that President Pervez Musharraf is hard put to control. With the barrage of violent statements that are bound to come from the opposition these rifts are going to be more difficult to paper over. Nawab Bugti, already 80 plus, wanted a heroic death for many personal, provincial and extra-provincial reasons. Whoever took military action against him has granted him his wish to be a martyr. This is a political nightmare that the PMLQ will find hard to handle here and now and Pakistan in the hereafter.

Whatever his personality and past, Nawab Bugti’s death is bound to become part of the heroic lore of Baloch history of resistance against the state since 1947 and strengthen the separatist emotion in the province. Since much of the Baloch struggle had combined with the all-Pakistan campaign against such phenomena as military rule and the cruel centralism of One Unit, it will find resonance with most Pakistanis — especially in the smaller provinces. His death will put an end to the case building by the government before going for the kill on Saturday. The case built by the state against the rebellious ‘sardars’ was not incredible: their insurgents were blowing up public assets and carrying out attacks against state personnel, they had organised ‘farari’ camps where Baloch warriors were trained and, finally, they were recipients of large sums of money, possibly sent in by India through Afghanistan. But now all this will sound like so much unconvincing history.

Baloch nationalism is based on a number of factors recognised by the textbooks but the most significant component is tribal resistance and honour. The sardari system provided leadership to this nationalism by upholding Baloch honour. While the Baloch politician developed flexible political skills, the Baloch sardar outshone him in the eyes of the Baloch people because of his inflexibility and an implacable assertion of Baloch rights. Of course, the Bugti-Marri-Mengal triumvirate of Baloch nationalism that developed over the years had its internal tensions and there was a tacit struggle for supremacy among the three. Needless to say, only the most radical could have won. It is in this framework that Nawab Bugti’s final choice of death has to be seen. And it is here that Islamabad has erred most grievously and might have to pay a high price for it. It has let Nawab Bugti win the final battle. He will now be the all-Balochistan symbol of resistance to Islamabad. If there is external interference in Balochistan it will only be strengthened.

Whoever in the national security establishment decided to eliminate Nawab Bugti physically is clueless about the force of politics, history and nationalism. Clearly, this was a politically inopportune moment for it. Most of what the opposition will say about the killing of Mr Bugti is going to gibe with what leading PMLQ politicians have felt: that the deadlock in Balochistan should not be resolved through military action. The ruling party is already bedevilled with rifts that President Pervez Musharraf is hard put to control. With the barrage of violent statements that are bound to come from the opposition these rifts are going to be more difficult to paper over. Nawab Bugti, already 80 plus, wanted a heroic death for many personal, provincial and extra-provincial reasons. Whoever took military action against him has granted him his wish to be a martyr. This is a political nightmare that the PMLQ will find hard to handle here and now and Pakistan in the hereafter.

Whatever his personality and past, Nawab Bugti’s death is bound to become part of the heroic lore of Baloch history of resistance against the state since 1947 and strengthen the separatist emotion in the province. Since much of the Baloch struggle had combined with the all-Pakistan campaign against such phenomena as military rule and the cruel centralism of One Unit, it will find resonance with most Pakistanis — especially in the smaller provinces. His death will put an end to the case building by the government before going for the kill on Saturday. The case built by the state against the rebellious ‘sardars’ was not incredible: their insurgents were blowing up public assets and carrying out attacks against state personnel, they had organised ‘farari’ camps where Baloch warriors were trained and, finally, they were recipients of large sums of money, possibly sent in by India through Afghanistan. But now all this will sound like so much unconvincing history.

Baloch nationalism is based on a number of factors recognised by the textbooks but the most significant component is tribal resistance and honour. The sardari system provided leadership to this nationalism by upholding Baloch honour. While the Baloch politician developed flexible political skills, the Baloch sardar outshone him in the eyes of the Baloch people because of his inflexibility and an implacable assertion of Baloch rights. Of course, the Bugti-Marri-Mengal triumvirate of Baloch nationalism that developed over the years had its internal tensions and there was a tacit struggle for supremacy among the three. Needless to say, only the most radical could have won. It is in this framework that Nawab Bugti’s final choice of death has to be seen. And it is here that Islamabad has erred most grievously and might have to pay a high price for it. It has let Nawab Bugti win the final battle. He will now be the all-Balochistan symbol of resistance to Islamabad. If there is external interference in Balochistan it will only be strengthened.

US General Abizaid says Pakistan Not Aiding Taliban

Abizaid says Pakistan not aiding Taliban

Online News, Islamabad

KABUL: A coalition air strike in southern Afghanistan killed a Taliban commander and 15 other militants, the U.S. military said.

A top American general, meanwhile, said insurgents are still using neighboring Pakistan as a base for infiltration.

Insurgents killed a NATO-led coalition soldier in southern Helmand province Sunday, NATO said. It did not provide the soldier’s nationality or details of the clash. Another NATO soldier and six Afghan troops were wounded when mortars hit their base in neighboring Kandahar province Sunday, NATO said.

Two French soldiers were killed and two others were wounded in the volatile east on Friday, while at least 13 other insurgents were killed in clashes with police and NATO in the south, the U.S. military said.

On Saturday, Canadian troops in the south mistakenly killed a policeman and wounded six other people, including two civilians, according to NATO.

Afghanistan is experiencing its worst bout of violence since the late-2001 ouster of the Taliban regime for hosting al-Qaida leader Osama bin Laden. More than 1,600 people, mostly militants, have died in the past four months, according to an Associated Press tally of violent incidents reported by U.S., NATO and Afghan officials.

Four rockets slammed into west Kabul on Sunday, one landing near a police station and another damaging a house, but nobody was injured, police said.

Gen. John Abizaid, commander of the U.S. Central Command, said militants are using Pakistan as a base from which to infiltrate into Afghanistan, but he said the Pakistani government is not conspiring with them.

"I think that Pakistan has done an awful lot in going after al-Qaida and it’s important that they don’t let the Taliban groups be organized in the Pakistani side of the border," he told reporters in Bagram, where the main U.S. military base in Afghanistan is located.

Abizaid said he "absolutely does not believe" accusations of collusion between Pakistan’s government and the resurgent Taliban rebels or other extremists.

"You do not order your soldiers in the field against an enemy in order to play some sort of a game with neighboring countries," he said.

Afghanistan repeatedly has criticized Pakistan for not doing enough to prevent Taliban militants and other rebels from crossing the poorly marked border.

Pakistan, a former Taliban supporter but now a U.S. ally in its war on terrorism, says it does all it can to tackle insurgents and has deployed 80,000 troops along the frontier.

Online News, Islamabad

KABUL: A coalition air strike in southern Afghanistan killed a Taliban commander and 15 other militants, the U.S. military said.

A top American general, meanwhile, said insurgents are still using neighboring Pakistan as a base for infiltration.

Insurgents killed a NATO-led coalition soldier in southern Helmand province Sunday, NATO said. It did not provide the soldier’s nationality or details of the clash. Another NATO soldier and six Afghan troops were wounded when mortars hit their base in neighboring Kandahar province Sunday, NATO said.

Two French soldiers were killed and two others were wounded in the volatile east on Friday, while at least 13 other insurgents were killed in clashes with police and NATO in the south, the U.S. military said.

On Saturday, Canadian troops in the south mistakenly killed a policeman and wounded six other people, including two civilians, according to NATO.

Afghanistan is experiencing its worst bout of violence since the late-2001 ouster of the Taliban regime for hosting al-Qaida leader Osama bin Laden. More than 1,600 people, mostly militants, have died in the past four months, according to an Associated Press tally of violent incidents reported by U.S., NATO and Afghan officials.

Four rockets slammed into west Kabul on Sunday, one landing near a police station and another damaging a house, but nobody was injured, police said.

Gen. John Abizaid, commander of the U.S. Central Command, said militants are using Pakistan as a base from which to infiltrate into Afghanistan, but he said the Pakistani government is not conspiring with them.

"I think that Pakistan has done an awful lot in going after al-Qaida and it’s important that they don’t let the Taliban groups be organized in the Pakistani side of the border," he told reporters in Bagram, where the main U.S. military base in Afghanistan is located.

Abizaid said he "absolutely does not believe" accusations of collusion between Pakistan’s government and the resurgent Taliban rebels or other extremists.

"You do not order your soldiers in the field against an enemy in order to play some sort of a game with neighboring countries," he said.

Afghanistan repeatedly has criticized Pakistan for not doing enough to prevent Taliban militants and other rebels from crossing the poorly marked border.

Pakistan, a former Taliban supporter but now a U.S. ally in its war on terrorism, says it does all it can to tackle insurgents and has deployed 80,000 troops along the frontier.

Crisis in Baluchistan

August 28, 2006 Christian Science Monitor

A rebel's killing roils Pakistan

By David Montero

QUETTA, PAKISTAN – For years, Nawab Mohammed Akbar Khan Bugti battled the Pakistan Army. The 80-year-old renegade hidden in the mountains of Balochistan became a legend in his fight for greater autonomy against what he saw as colonial brutality.

Bugti was both hated and revered. But as a former federal minister and governor, he symbolized a political as well as a violent struggle. And his death this weekend, during a fierce three-day battle that left more than 30 dead, could prove a serious blow to Pakistan's stability.

"This is not a good sign," says Samina Ahmed, South Asia director of the International Crisis Group. "Just a few years ago [Nawab Bugti] was talking to the government. Keeping that door open was the way to go. Now that door has been slammed shut."

Bugti's death could also reverberate in the region, some analysts say. The Balochis are spread across several countries, with millions living in parts of Iran and Afghanistan that border Pakistan.

"They will provide sanctuary to Baloch militants. There will be a lot of sympathy," says Lt. Gen. (ret.) Talat Masood, a defense analyst in Islamabad.

For complete article, click here

For BBC report on Baluchistan by Zafar Abbas, click here

A timeline - Akbar Bugti's Political Profile at The News

A rebel's killing roils Pakistan

By David Montero

QUETTA, PAKISTAN – For years, Nawab Mohammed Akbar Khan Bugti battled the Pakistan Army. The 80-year-old renegade hidden in the mountains of Balochistan became a legend in his fight for greater autonomy against what he saw as colonial brutality.

Bugti was both hated and revered. But as a former federal minister and governor, he symbolized a political as well as a violent struggle. And his death this weekend, during a fierce three-day battle that left more than 30 dead, could prove a serious blow to Pakistan's stability.

"This is not a good sign," says Samina Ahmed, South Asia director of the International Crisis Group. "Just a few years ago [Nawab Bugti] was talking to the government. Keeping that door open was the way to go. Now that door has been slammed shut."

Bugti's death could also reverberate in the region, some analysts say. The Balochis are spread across several countries, with millions living in parts of Iran and Afghanistan that border Pakistan.

"They will provide sanctuary to Baloch militants. There will be a lot of sympathy," says Lt. Gen. (ret.) Talat Masood, a defense analyst in Islamabad.

For complete article, click here

For BBC report on Baluchistan by Zafar Abbas, click here

A timeline - Akbar Bugti's Political Profile at The News

Saturday, August 26, 2006

Bugti Killed in a military operation: This is pure murder and blood is on Musharraf's hands

BBC - August 26, 2006

Pakistan says key rebel is dead

Tribal leader Nawab Akbar Bugti has been killed in a battle between tribal militants and government forces in Balochistan province, Pakistan says.

The battle near his mountain hideout in south-west Pakistan also caused heavy casualties on both sides, reports say.

More than 20 soldiers and at least 30 rebels died, officials say.

The octogenarian has been at the head of a tribal campaign to win political autonomy and a greater share of revenue from Balochistan's gas reserves.

"It is confirmed, Nawab Bugti has been killed in an operation," Information Minister Mohammad Ali Durrani told Reuters news agency.

The battle reportedly took place near the town of Dera Bugti, not far from Mr Bugti's hideout.

One report said government forces had targeted between 50 and 80 rebel fighters, after being led to the area by an intercepted satellite phone call.

Mineral-rich

Balochistan is Pakistan's biggest province, and is said to be the richest in mineral resources. It is a major supplier of natural gas to the country.

For decades, Baloch nationalists have been critical of the central government in Islamabad, accusing it of depriving the province of its due.

They say the government took away income from natural gas and other resources, while spending only a trivial amount on the province.

For Newsline's interview with Akbar Bugti, click here

For Political profile of Akbar Bugti in Daily Times, click here

Pakistan's balancing act

Excerpts from

Pakistan's Awkward Balancing Act on Islamic Militant Groups

By Pamela Constable

Washington Post Foreign Service; August 26, 2006; A10

ISLAMABAD, Pakistan -- For the past five years, Pakistan has pursued a risky, two-sided policy toward Islamic militancy, positioning itself as a major ally in the Western-led war against global terrorism while reportedly allowing homegrown Muslim insurgent groups to meddle in neighboring India and Afghanistan.

"The conundrum for the military still persists," said Talat Masood, a retired Pakistani army general. "The question always is, should we totally ban these organizations or keep them for later use?" Although the government has "selectively" prosecuted extremist groups, he said, "at the conceptual level, it has deliberately followed an ambiguous policy."

The basic problem for Pakistan's president, Gen. Pervez Musharraf, is that he is trying to please two irreconcilable groups. Abroad, the leader of this impoverished Muslim country is frantically competing with arch-rival India, a predominantly Hindu country, for American political approval and economic ties. To that end, he has worked hard to prove himself as a staunch anti-terrorism ally.

But at home, where he hopes to win election in 2007 after eight years as a self-appointed military ruler, Musharraf needs to appease Pakistan's Islamic parties to counter strong opposition from its secular ones. He also needs to keep alive the Kashmiri and Taliban insurgencies on Pakistan's borders to counter fears within military ranks that India, which has developed close ties with the Kabul government, is pressuring its smaller rival on two flanks.

Until recently, Musharraf had handled this balancing act with some success, Pakistani and foreign experts said. He formally banned several radical Islamic groups while quietly allowing them to survive. He sent thousands of troops to the Afghan border while Taliban insurgents continued to slip back and forth. Meanwhile, his security forces arrested more than 700 terrorism suspects, earning Western gratitude instead of pressure to get tougher on homegrown violence.