Dawn, April 1, 2006

Manmohan Singh’s peace offer

By Kuldip Nayar

IT should have been Pakistan’s initiative. But some of us Indians took it. Nearly 50, including two Lok Sabha members from Orissa and one former Delhi chief justice, laid flowers in Lahore at the Shadman Chowk, the spot where Bhagat Singh and his two comrades, Sukhdev and Rajguru, were hanged by the British 75 years ago. We delayed the ceremony by a day because of the Pakistan Day celebrations on March 23.

We did not publicise the Bhagat Singh martyrdom day purposely because some of my liberal friends in Pakistan had warned me that religious parties might react adversely. I had reason to suspect some outlandish reaction because when I had approached the Punjab (Pakistan) government some years ago for archival material for my book on Bhagat Singh they had told me that “they were afraid lest they should get entangled in the Sikh problem.”

After all, the ceremony was the first of its kind after the formation of Pakistan, although Bhagat Singh was a national hero. A few people from Shadman colony strayed in and watched what we did. But the friends I invited in Pakistan were not able to make it. Most of them were in Karachi to attend the World Social Forum. Still, there were many who could have come but did not. Communists were conspicuous by their absence. I suspect people, on the whole, were afraid.

This is in line with my reading of liberals in the subcontinent. They are willing to strike but afraid to wound. I saw how they caved in in my own country during the emergency when there was not even army rule. Today those very people are part and parcel of the government and serve as a channel for pressure and prize.

In the afternoon, there was a function in memory of the martyrs in the subcontinent. The hall was packed to capacity. However, the organisers were particular not to mention Bhagat Singh’s name on the invitation card. They did not want to come into the open. Still, it was brave of them.

My assessment over the years is that fear stalks the land called Pakistan. People are afraid to speak out in public what they say in private. None likes the “uniformed democracy.” Yet, none dares to hold a meeting or demonstration to point out that the dumb show of democracy is limited to what is permitted. No doubt, the press is free. People’s movement is free. But no party agitates against the ban on open political activity. Protest is confined to mere press statements.

What torments me is that the public is getting reconciled to the system of partial freedom. There are no stirrings to challenge it. Many liberals have joined the long list of beneficiaries. Thousands of people are willing to come to streets to protest on religious matters but none in the name of democracy. The control by the army and its agencies is so deep and so pervasive that the 2007 election may turn out to be another farce. Candidates to be elected may be sifted from the rest on the day of their nomination. It has happened in the past. Some may still be returned. But they will be nowhere near the majority. A free and fair election is difficult to envisage in Pakistan, whatever the US may declare.

I recall when I interviewed the then President, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, in the beginning of 1972, asking him whether the army could come back. He laughed and said: “My people will come on the streets to fight the tanks.” After Pakistan adopted the 1973 Constitution, he said in a speech that the people, especially the brightest and the best among them, would protect it “with their blood and with their lives.” That did not happen. General Zia-ul Haq walked in easily. Pakistan’s long history of military rule has sapped people’s energy as well as their will to resist. Feudal as Pakistan society has been, it has become more feudal and less democratic even in its day-to-day life.

Nonetheless, if posterity were ever to record the reasons for the loss of democracy in Pakistan, India’s attitude would be blamed the most. From day one, the latter’s effort has been how to humiliate Pakistan. A country whose founder died early without building institutions was burdened with responsibilities of security. New Delhi’s fear did not allow Islamabad to settle down.

The Pakistan policy in India is framed by bureaucrats and implemented by bureaucrats who have not changed in the last 50 years. Unfortunately, at a crucial time between the two countries, the foreign office had ministers who were ex-bureaucrats. Nothing came out of meetings with Pakistan, which was equally obstructive and even obscurantist. The tragedy is that both New Delhi and Islamabad are guided by people whose minds are tainted.

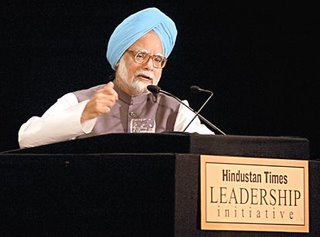

When Prime Minister Manmohan Singh offered Pakistan a peace and friendship treaty, he was out of Delhi, away from advisers and experts. South and North Blocks are too oppressively intolerant to let a different point of view see the light of day. The issue of the Siachen Glacier and Sir Creek which Manmohan Singh wants settled should have been out of the way long ago.

The controversy over the Baglihar dam would not have arisen if New Delhi had been transparent in its construction plans. After Manmohan Singh’s offer, confidence-building measures should be easier to settle. But my worry is that advisers and experts are going to come in the way because they are far distant from the prime minister’s thinking.

I wish we could separate Kashmir from the normalization with Pakistan. We have vainly tried to do so for years. Islamabad’s entire policy has been against de-linking because Kashmir has continued to be the point over which anti-India sentiments have been aroused. However, Manmohan Singh has himself suggested a way out. His ideas of helping Kashmir jointly can be given concrete shape by handing over all subjects, except defence, foreign affairs and communications to the Kashmiris on both sides of the border. The border should be made soft for people living in the two parts. They should be allowed to have their own air service to connect foreign countries or anything else jointly.

But for selling such a formula, there is need for people-to-people contact. Unfortunately, it is lessening because of visa restrictions. Whatever the statements, the governments in both countries issued fewer visas in recent months.

The inconveniences have increased manifold. The CID still bothers the people who meet visitors from the other side. Manmohan Singh’s offer has little meaning if the walls on the border are to remain as they are.

The writer is a leading columnist based in New Delhi.

No comments:

Post a Comment