Dawn, February 5, 2006

Promoting the reading habit

By Anwar Syed

Book buying is not common. Prices are too high for most people. Publishers are cautious, and most of them are reluctant to publish serious books. Normally, they will print no more than a 1,000 copies of any title, and often only 500, which they say it takes several years to sell. Libraries, that are the larger buyers in many countries, don’t have the money for new acquisitions. Efforts are being made to popularize reading in Pakistan.

I BEGIN this article with excerpts from the recollections of Paris Minton, a black American, as he revisits his childhood and adolescence in a segregated neighbourhood in a small town in Louisiana (US) in the 1940s.

“I entered school at the age of six. On the first day I heard Miss Randolph (teacher) read a story, and I knew that books were to be my destiny. By the age of eight I was alone in the school library, reading everything I could. By the time I was 15 I had read the Bible and every book anyone had in our neighbourhood.

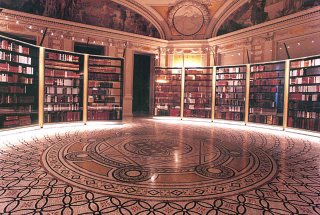

“There was a public library in the white part of town; coloureds couldn’t go inside. I would go and sit on a bench outside, rereading old books like Uncle Tom’s Cabin. One day the librarian, Miss Dowling, came out and asked me what I was doing. ‘Reading,’ I said proudly. ‘I don’t believe you,’ she said, and then asked me to read a sentence. I read the first page and then the second. When I was through, Miss Dowling led me into a large room in the library, lined to the ceiling with shelves packed with neat rows of books. ‘It is beautiful, I have never seen anything like it,’ I said. ‘Of course, you haven’t. It is because this is a white library. These books are not meant for you. These books were written by white people for white people. There will be no library card for you, so you can stop sitting out in front.

“I went home in tears. I cried that night and all the next day. Miss Dowling had broken my heart. For months I moped around, and then one day I was on a train bound for San Francisco, because I had heard that in California black folks could go into any library, get library cards, and borrow books to take home. It was cold in Frisco, but I read a book a day in the first year. Libraries still make my heart race. There is nothing like a book.” (Fearless Jones by Walter Mosley, 2001.)

Not all young people are as motivated or enterprising as Paris was. Many of them at the age of six in Pakistan will barely read the required Urdu primer. But there are families that are intellectually inclined and their kids see their older brothers and sisters read and discuss books. Soon enough they too will begin to read beyond the required school texts. Reading will become a habit.

A certain amount of nudging and encouragement may help young people to develop an enduring interest in reading. I know a little fellow who is not quite six yet. He and his grandmother have made a deal. She gives him one dollar for every children’s book he reads. He is reading one book a week and his “kitty” is filling up.

I want to say a word about the role of libraries in all of this. I live in an urban district, called Fairfax County, in northern Virginia. It has a population of a little over one million with some 370,000 households. It maintains 10 “regional” libraries, each containing more than half a million volumes, in the larger towns, and 10 smaller community libraries. Each of the regional libraries is open seven days a week and services several hundred users every day. The staff includes a variety of specialists. The children’s librarian organizes programmes to enliven their interest in reading and learning. Public interest may be gauged from the fact, among others, that the circulation desk maintains a long waiting list of persons who want to borrow this or that book which has been named as one of the “best sellers” for the week.

Television has become a great distraction, drawing persons away not only from conversation but also from reading. Careful parents limit their children’s television viewing to an hour or two each day. It is a good idea for father or mother to sit down and read something together with their child.

The “blue collar” workers in most places are not much given to reading. If they buy a newspaper at all, they will focus on sports pages. Quite a few in the middle and upper classes will take in news of the stock market in addition to sports and the front-page headlines. A smaller number will read the editorial and opinion pages. Women in these classes read magazines, but many more of them than men read books also. Retired men, more than working men, turn to reading books.

It seems that more people in Britain read books and/or magazines than they do in Europe and America. A survey in 2002 reported that half of the adult population had read five or more books in the preceding 12 months, but that a quarter had not read any. Seventy per cent of 16 to 24-year olds had read a magazine, and 33 per cent had read fiction. Forty-three per cent of the 55 to 64-years olds had also read fiction. Britons were spending 2.6 billion pounds a year on buying books.

I don’t have figures for readers of books and magazines in Pakistan. Ms Ameena Saiyid, managing director of Oxford University Press in Karachi, says ours is not a reading culture. Officials in the ministry of education and the National Book Foundation say the same. It is then likely that the numbers, if available, would turn out to be low.

The status of libraries in the country could be one indicator of the size of readership. Comparative figures may help provide a perspective. The United States has close to 32,000 public libraries, and the Library of Congress alone keeps some 90 million items. Fifteen years ago, Israel had 3,420 libraries for a population of five million. Tanzania, one of the poorest countries in the world, has 3,200 rural libraries. According to a survey done in 1990, Pakistan, by contrast, had 1,430 libraries, including the academic ones, with a total collection of about 15 million books. Holdings of public libraries are quite modest. The National Library of Pakistan has a collection of about 120,000. Many of them are nothing more than reading rooms that offer a few newspapers. Rural libraries are virtually non-existent. Of the 171,000 schools in the country only 481 have libraries.

Book buying is not common. Prices are too high for most people. Publishers are cautious, and most of them are reluctant to publish serious books. Normally, they will print no more than a 1,000 copies of any title, and often only 500, which they say it takes several years to sell. Libraries, that are the larger buyers in many countries, don’t have the money for new acquisitions.

Efforts are being made to popularize reading in Pakistan. Book fairs and exhibitions are held. The National Book Foundation has reportedly launched an intriguing scheme. It will sponsor a book club whose members will be able to buy books at half the list price at designated 47 shops while the Foundation pays the other half. Those who buy books at one of its own stores in 22 cities will qualify for an additional five per cent discount.

Once in a while private individuals take interest in promoting the reading habit. I have heard of Anthony D’Silva, a teacher in Goa (India), who has, upon the advice of his local priest, set up a number of sheds in his own and some of the neighbouring villages with newspaper stands to which young people are flocking. I don’t know if there are counterparts of D’Silva in Pakistan. I have heard also that at one time, until the 1970s, many informal area libraries flourished in Karachi, but with the advent of television and video they have apparently languished and eventually disappeared.

Entertainment is one of the more powerful motivations for reading. Finding and reading a good story can be exciting for a child. It is the beginning of forming the reading habit. But fiction can continue to be a thing of joy even after he has grown up. It detaches him both from the frenzies and the drab routines of actual living. As Paris Minton said, a book is a wonderful thing not only for amusement but also for one’s enlightenment.

Not all books are equally engaging. Many a reader has to struggle through books on technical subjects and those offering philosophical speculation. But surprisingly enough, that can happen even with books that you have picked up in the hope of entertaining yourself. I have read about 150 historical and detective novels during the last five years, and I found one third of them to be more annoying than amusing.

More women than men have of late been writing detective novels In many of them more than a hundred pages go by and the crime (usually murder) has not yet taken place. The author enters the memory lane, or becomes introspective, and proceeds to tell me of her/his own early exploits plus her/his predispositions, passions, and prejudices. She will take me into a house and describe, in overwhelming detail, fittings and fixtures, carpets, drapes, furniture, layout, colour scheme, paintings, books, crockery and cutlery, and numerous other things in the interior, and the grass, bushes, and flowers in the garden.

I have learned the art of beating such writers at this game: I look at these unwanted explorations and descriptions diagonally, not horizontally, and keep turning pages until the author returns to the detective, his investigation, suspects he is interrogating, and the clues he is finding.

There are those of us who do not enjoy “small talk.” Interesting persons who are fun to talk with are not always available. Reading enables one to have the company of stimulating people and, if one prefers, that of great minds. For many of us life in retirement, when one has time on one’s hands, would be utterly intolerable if one did not have the opportunity to read and, in the case of some of us, reason to write any more.

The writer is emeritus of political science at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, US. Email: answarsyed@cox.net

No comments:

Post a Comment