Near East South Asia Center for Strategic Studies, National Defense University - August 2020

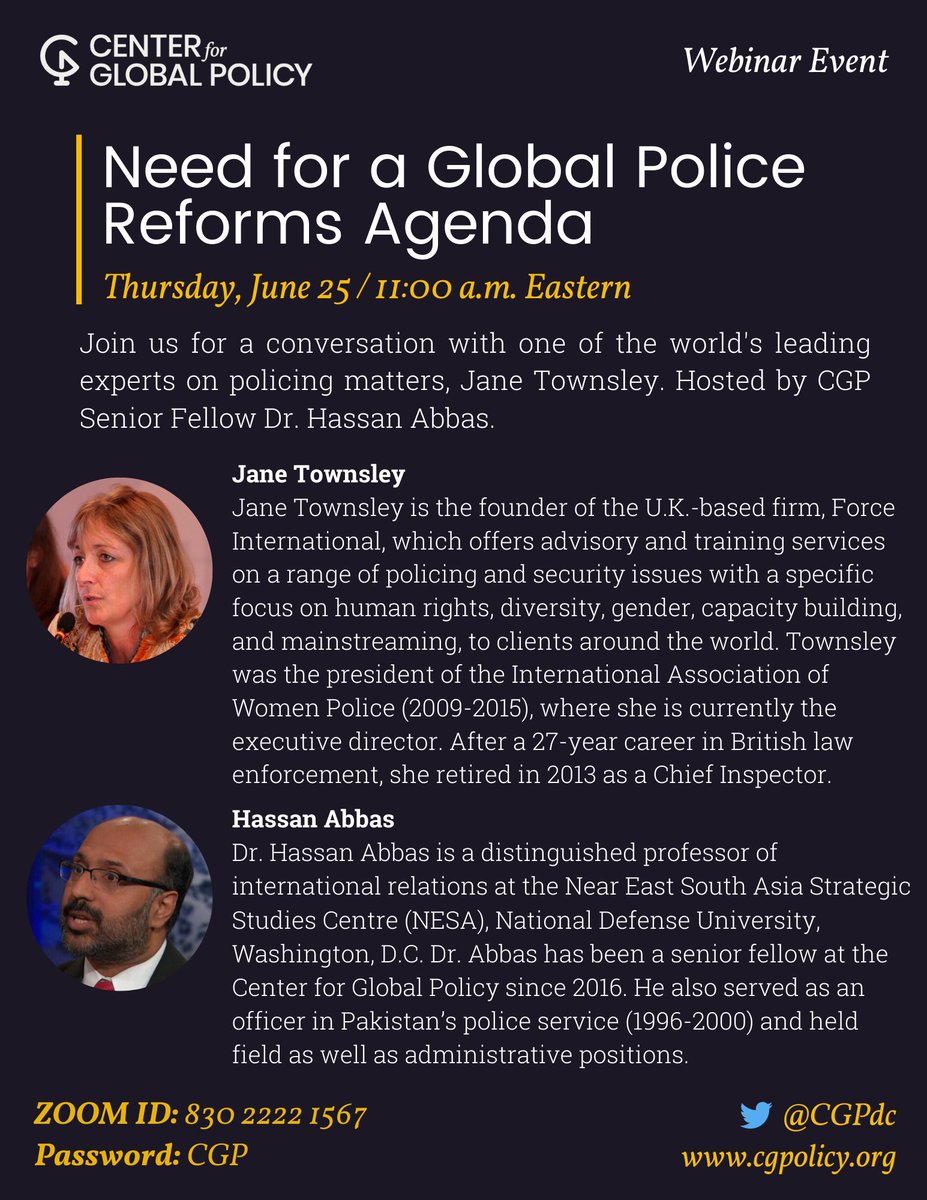

In the fifth segment of NESA South Asia Interview Series, Professor Hassan Abbas interviews Professor Qamar-ul Huda who is a non-resident fellow at The Atlantic Council in Washington, D.C and an adjunct associate professor at Georgetown University. He formerly worked as a senior policy advisor to the U.S. State Department Secretary’s Office.

HASSAN ABBAS: Congratulations on your recent publication “A Critique of Countering Violent Extremism Programs in Pakistan” (Center for Global Policy, July 2020). What are the core findings from the report that are crucial for CVE practitioners today? What are your top 3-5 findings?

QAMAR-UL HUDA: I think the top five findings from the policy report are the following:

1. In Pakistan – a frontline state in the war of terrorism- Countering Violent Extremism (CVE) policies and programs are still fundamentally controversial, misunderstood, and strongly criticized by local human rights groups and religious leaders. Pakistan state institutions and civil society organizations have implemented a variety of CVE programs but there have been no measures of the programs’ effectiveness or impact analysis, and this raises concerns about the fundamental nature of CVE programs.

2. One area I discovered in researching for the report was that Pakistani NGOs and civil society stakeholders raised serious concerns regarding CVE thinking and assumptions on radicalization and extremism because they felt these ideas were imported by the global community of researchers. These assumptions were never debated internally by Pakistan’s academic research community. The notion of radicalism was not contested but there were repeated opinions on whether there could be a more nuanced local cultural understanding. That is to say Pakistani NGO organizations and CVE workshop participants repeatedly expressed having grievances against inept, oppressed governments or government policies or international actors which did not explicitly make them radicals. Also, there were tremendous amount of push-back on the fact that Pakistani CVE programs over-emphasized religious figures or religious organizations, and this approach’s primary focus on religion lacked a comprehensive scheme.

3. CVE Programs were designed and implemented with a heavy emphasis on counter-messaging to the propaganda of the violent extremists. Strategic communications to interfere, manipulate, and disrupt the extremists’ propaganda meant supporting religious leaders to counter new narratives but there was never a strategic plan in place to monitor or evaluate the effectiveness of the counter-messaging or an understanding of its impact. This report discovered project evaluations but there was no single database or single institute supervising the monitoring or evaluations of CVE counter-messaging to inform better practices.

4. As “CVE” became more mistrusted and tainted in Pakistan, NGOs and civil society groups were put at risk for taking part in these activities and receiving international aid. NGOs implementing CVE programs – whether sponsored by Pakistan government or by international donors – risk falling under suspicion of contributing to ethnic, religious and sectarian conflicts. CVE funds received by NGOs were questioned by intelligence on how they were able to access CVE funds and how much of the funds were actually used for CVE activities. The suspicion undermined the credibility of NGOs who were attempting to bring grassroots leaders to learn about CVE counter-messaging.

5. Within the global CVE research community there is a consensus, for over eight years, that any successful CVE policy will be based upon multidisciplinary approaches and multi-agency cooperation. Attempts to combat the totalitarian nature of violent extremist groups require a holistic understanding of local sectarian grievances and structural issues such as energy, access to water, housing, quality of education, healthcare services. But, in Pakistan’s CVE policy and/ or programming, the report did not see multiagency cooperation or international funded program coordination. However, Pakistan has a unique opportunity to correct its course by building and developing upon its original national strategy.

HASSAN ABBAS: The report appears to be cautioning CVE experts not to play with religious narratives and argues that engaging religious scholars to challenge and condemn violent extremism may not in reality be an effective or appropriate CVE practice. Kindly elaborate this point further as most Muslim states are heavily engaged in this exercise.

QAMAR-UL HUDA: Even before the White House Summit on CVE in February, 2014, the global CVE research and policy community were intent on finding and funding “moderate Muslim religious networks” (Rand Report), “supporting non-violent jihadi Salafi groups” (Graeme Wood), “to collaborate with global Salafism (William McCants and Shadi Hamid), and leverage the rising middle class Shi’ites in the Middle East against the Hezbollah movement and the ‘Ulama of Iran (Vali Nasr).

The role of religion in countering violent extremism — especially during the peak of Daesh’s rise after the capture of Mosul, Iraq, in 2014 — was tied to an abstract computation of funding a religious leader’s organization, building trusted networks, and supporting the dissemination of CVE messaging about peace and pluralism. Considering religious engagement as an aspect of security was problematic to some, but others argued that the stakes were too high to ignore the role of religious actors in CVE activities.

HASSAN ABBAS: The report appears to be cautioning CVE experts not to play with religious narratives and argues that engaging religious scholars to challenge and condemn violent extremism may not in reality be an effective or appropriate CVE practice. Kindly elaborate this point further as most Muslim states are heavily engaged in this exercise.

QAMAR-UL HUDA: Even before the White House Summit on CVE in February, 2014, the global CVE research and policy community were intent on finding and funding “moderate Muslim religious networks” (Rand Report), “supporting non-violent jihadi Salafi groups” (Graeme Wood), “to collaborate with global Salafism (William McCants and Shadi Hamid), and leverage the rising middle class Shi’ites in the Middle East against the Hezbollah movement and the ‘Ulama of Iran (Vali Nasr).

The role of religion in countering violent extremism — especially during the peak of Daesh’s rise after the capture of Mosul, Iraq, in 2014 — was tied to an abstract computation of funding a religious leader’s organization, building trusted networks, and supporting the dissemination of CVE messaging about peace and pluralism. Considering religious engagement as an aspect of security was problematic to some, but others argued that the stakes were too high to ignore the role of religious actors in CVE activities.

For complete interview, click here

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/66884083/GettyImages_1216490741.0.jpg)