Daily Times, April 1, 2006

‘92% of Pakistanis oppose violent cartoon protests’

LAHORE: At least 92 percent of Pakistanis support peaceful demonstrations to protest the publication of cartoons of the Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him) and oppose violent demonstrations.

A poll was recently conducted by the Pakistan Institute for Peace Studies (PIPS) in Islamabad, Lahore and Peshawar to gauge public opinion about the publication of the cartoons and the subsequent rioting that killed around 10 people. The cartoons were first published in Danish newspaper Jyllands-Posten and later in publications across Europe.

Around 97 percent of those interviewed felt that the publication of the cartoons was a violation of freedom of expression. Ninety-five percent of those surveyed opposed attacking embassies of European countries in reaction to the publication of cartoons in newspapers there. Almost everyone also opposed the publication of the holy personages of other religions in retribution to the Prophet’s (PBUH) cartoons. However, 62.26 percent favoured the economic boycott of countries where the cartoons had been published, while round 52 percent called for suspending all diplomatic ties with such countries. staff report

Watandost means "friend of the nation or country". The blog contains news and views that are insightful but are often not part of the headlines. It also covers major debates in Muslim societies across the world including in the West. An earlier focus of the blog was on 'Pakistan and and its neighborhood' (2005 - 2017) the record of which is available in blog archive.

Friday, March 31, 2006

Thursday, March 30, 2006

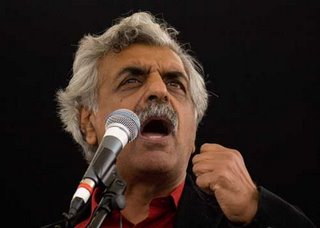

The Karachi Social Forum: Tariq Ali's viewpoint

Counterpunch: March 28, 2006

NGOs or WGOs?: The Karachi Social Forum

By TARIQ ALI

in Karachi, Pakistan.

While we were opening the World Social Forum in Karachi last weekend with virtuoso performances of sufi music and speeches, the country's rulers were marking the centenary of the Muslim League [the party that created Pakistan and has ever since been passed on from one bunch of rogues to another till now it is in the hands of political pimps who treat it like a bordello] by gifting the organisation to General Pervaiz Musharaf, the country's uniformed ruler.

The secular opposition leaders, Nawaz Sharif and Benazir Bhutto, who used to compete with each other to see who could amass more funds while in power, are both in exile. To return home would mean to face arrest for corruption. Neither is in the mood for martyrdom or relinquishing control of their organizations. Meanwhile, the religious parties are happily implementing neo-liberal policies in the North-West Frontier province that is under their control. Incapable of catering to the real needs of the poor they concentrate their fire on women and the godless liberals who defend them.

The military is so secure in its rule and the official politicians so useless that 'civil society' is booming. Private TV channels, like NGOs, have mushroomed and most views are permissible (I was interviewed for an hour by one of these on the "fate of the world communist movement") except a frontal assault on religion or the military and its networks that govern the country. If civil society posed any real threat to the elite, the plaudits it receives would rapidly turn to menace.

It was, thus, no surprise that the WSF, too, had been permitted and facilitated by the local administration in Karachi. It is now part of the globalized landscape and helps backward rulers feel modern. The event itself was no different from the others. Present are several thousand people, mainly from Pakistan, but with a sprinkling of delegates from India, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, South Korea and a few other countries.

Absent was any representation from China's burgeoning peasant and workers movements or its critical intelligentsia. Iran, too, was unrepresented as was Malaysia. The Israeli enforcers who run the Jordanian administration harassed a Palestinian delegation. Only a handful of delegates managed to get through the checkpoints and reach Karachi. The huge earthquake in Pakistan last year had disrupted many plans and the organizers were not able to travel and persuade people elsewhere in the continent to come. Otherwise, insisted the organisers, the voices of Abu Ghraib and Guantanamo and Fallujah would have been heard.

The fact that it happened at all in Pakistan was positive. People here are not used to hearing different voices and views. The Forum enabled many from repressed social layers and minority religions to assemble make their voices heard: persecuted Christians from the Punjab, Hindus from Sind, women from everywhere told heart-rending stories of discrimination and oppression.

Present too was a sizeable class-struggle element: peasants fighting against the privatization of military farms in Okara, the fisher-folk from Sind whose livelihoods are under threat and who complained about the great Indus river being diverted to deprive the common people of water they had enjoyed since the beginning of human civilization thousands of years ago, workers from Baluchistan complaining about military brutalities in the region.

Teachers who explained how the educational system in the country had virtually ceased to exist. The common people who spoke were articulate, analytical and angry, in polar contrast to the stale rhetoric of Pakistan's political class. Much of what was said was broadcast on radio and television with the main private networks---Geo, Hum and Indus--- vying with each other to ensure blanket coverage.

And so the WSF like a big feel-good travelling road show came to Pakistan and went. What will it leave behind? Very little, apart from goodwill and the feeling that it has happened here. For the fact remains the elite dominates that politics in the country. Little else matters. Small radical groups are doing their best, but there is no state-wide organisation or movement that speaks for the dispossessed. The social situation is grim, despite the massaged statistics circulated by the World Bank's Pakistani Prime Minister Shaukat Aziz.

The NGOs are no substitute for genuine social and political movements. They may be NGOs in Pakistan but in the global scale they are WGOs (Western Governmental Organizations), their cash-flow conditioned by restricted agendas. It is not that some of them are not doing good work, but the overall effect of this has been to atomize the tiny layer of left and liberal intellectuals. Most of these men and women (those who are not in NGOs are embedded in the private media networks) struggle for their individual NGOs to keep the money coming; petty rivalries assumed exaggerated proportions; politics in the sense of grass-roots organisation is virtually non-existent. The Latin American model as emerging in the victories of Chavez and Morales is a far cry from Mumbai or Karachi.

Tariq Ali is author of the recently released Street Fighting Years (new edition) and, with David Barsamian, Speaking of Empires & Resistance. He can be reached at: tariq.ali3@btinternet.com

4 Pakistani women fighter pilots graduate from Air Force Academy

Daily Times, March 31, 2006

PAF’s first 4 women fighter pilots graduate

RISALPUR: Defence services are a challenging and daunting job but our aim to join Pakistan Air Force (PAF) is to serve Pakistan, said Saba Khan, one of the four women general duty (GDP) pilots who are the first women to earn flying badges from PAF.

Talking to reporters after the passing out parade at the PAF Academy, Khan, flanked by Nadia Gul, Mariam Khalil and Saira Batool, said that they were proud of joining PAF as cadets. They urged women to join air force “because it is an attractive and honourable service”.

The four women pilots joined the PAF Academy in October 2002 and during three-year stay they had gone through demanding general service training. Two of them are from Quetta, one from Peshawar and one from Bahawalpur. Air Commodore Abid Khawaja told reporters that the women pilots performed well in all fields during their training. He said although they faced some difficulties at the start of their training, they made rapid improvement to overcome all hurdles with hard work and dedication.

He said they had gone through strenuous academic education and rigorous flying training on MFI-17 Super Mushshak and T-37 Jet aircraft. He added that three more women pilots were getting training at the PAF Academy under the 117th GD Course and would pass out within six months. Khawaja said the induction of women GD pilots had been stopped. “We want to check operational fitness of these women officers after which a decision about the induction of more women officers would be taken,” he said.

Vice Chief of the Army Staff General Ahsan Saleem Hayat was the chief guest at the graduation ceremony. The VCOAS staff awarded the Quaid-e-Azam Banner to the 4th Squadron. The trophy for the best performance in General Service Training went to Cadet Taimoor Khan Jadoon. Female Cadet Nadia Gul was awarded with Asghar Hussain Trophy for best performance in academics. The Chief of Air Staff’s Trophy for Best Performance in Flying was lifted by Iraj Jamal. The graduation ceremony also included display of immaculate and thrilling aerobatics by the flyers of Karakoram-8 (K-8 Academy Hawks) and T-37 aircraft (Sherdils). APP

PAKISTAN: FORMER BIN LADEN AIDE AND MILITANT FIGHTS FOR LIFE AFTER ATTACK

Karachi, 29 March (AKI) - (by Syed Saleem Shahzad) - The leader of one of Pakistan's most feared militant groups, who was also once a close aide to Osama bin Laden, is currently in critical condition in a Rawalpindi hospital after surviving an attempt on his life. Maulana Fazlur Rehman Khalil, the chief of the banned Harkat-ul-Mujahadeen, was dumped in front of a mosque in the outskirts of the Pakistani capital Islamabad.

"Don't call it an accident," said Harkat-ul-Mujahadeen's official spokesperson Sultan Zia in an interview with Adnkronos International (AKI). "It was a fully managed episode," he said.

The militant organisation, which was then known as Harkat-ul-Ansar, was blacklisted as a terror group by the US State Department in 1994.

Pakistan's president Pervez Musharraf banned the organisation in 2001 and Khalil has kept a low profile ever since.

"Fazlur Rehman Khalil does not have any personal feud against anybody," said Zia. "In the incident it seems that a few people were chasing him and when he reached Tarnol and offered his Magrib prayers on Tuesday evening at a prayer's place (not a proper mosque), around five people kidnapped him and his driver. They beat him mercilessly and suffocated him. Maulana Fazlur Rehman Khalil was unconscious and so they believed that he was dead and left him and his driver with their hands tied with ropes," said Zia.

"It was coincidence that people nearby found them and provided first aid so that they survived," Zia maintained.

According to Sultan Zia, the abductors were repeatedly saying that they were after Khalil for quite some time but they did not have a chance to get him.

Fazlur Rehman Khalil was one of the oldest jihadi leaders in Afghanistan, famed for fighting against the Soviets. He founded Harkat after the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan and fought alongside the mujahadeen forces.

Harkat was respected in jihadi circles for its role in the defeat of the communist Afghan Army of Afghanistan in the south-eastern Afghan province of Khost where the militant group then seized control in 1991. Khost was the first major city which fell to the mujahadeen fighters. The Harkat fighters also fought along side with the fugitive Taliban leader Maulana Jalaluddin Haqqani.

When the United States under the administration of Bill Clinton fired cruise missiles to target bin Laden in Afghanistan in 1998, Kandahar was attacked in a bid to kill the al-Qaeda leader and Khost was attacked to destroy the bases of the Harkat-ul-Mujahadeen in the province.

After the attacks, bin Laden held a press conference in Afghanistan, while at the same time Khalil held a separate press conference in Pakistan in which he supported bin Laden's statement to attack American interests all over the world. At the press conference, he also asserted that the Harkat-ul-Mujahadeen would take revenge on the US attack on Afghanistan.

After the 1998 attacks, Khalil also went on to hold many seminars in Pakistan in favour of bin Laden. The al-Qaeda leader provided him with large sums of money which he is believed to have embezzeled, after which he fell out of favour with bin Laden.

After the September 11, 2001 attacks on the United States, the FBI sought to interrogate him. It is believed they managed to do so and that Khalil was injected with various medicines which eventually affected his mental health. He often complained of physical problems as a result of the FBI interrogation

Sources said that although Khalil reportedly had abandoned all jihadi activities, the Pakistani authorities recently became suspicious about his activities and have interrogated him regarding his alleged ties with the Taliban fighters in the tribal region of Waziristan which borders Afghanistan.

(Syed Saleem Shahzad)

Karachi, 29 March (AKI) - (by Syed Saleem Shahzad) - The leader of one of Pakistan's most feared militant groups, who was also once a close aide to Osama bin Laden, is currently in critical condition in a Rawalpindi hospital after surviving an attempt on his life. Maulana Fazlur Rehman Khalil, the chief of the banned Harkat-ul-Mujahadeen, was dumped in front of a mosque in the outskirts of the Pakistani capital Islamabad.

"Don't call it an accident," said Harkat-ul-Mujahadeen's official spokesperson Sultan Zia in an interview with Adnkronos International (AKI). "It was a fully managed episode," he said.

The militant organisation, which was then known as Harkat-ul-Ansar, was blacklisted as a terror group by the US State Department in 1994.

Pakistan's president Pervez Musharraf banned the organisation in 2001 and Khalil has kept a low profile ever since.

"Fazlur Rehman Khalil does not have any personal feud against anybody," said Zia. "In the incident it seems that a few people were chasing him and when he reached Tarnol and offered his Magrib prayers on Tuesday evening at a prayer's place (not a proper mosque), around five people kidnapped him and his driver. They beat him mercilessly and suffocated him. Maulana Fazlur Rehman Khalil was unconscious and so they believed that he was dead and left him and his driver with their hands tied with ropes," said Zia.

"It was coincidence that people nearby found them and provided first aid so that they survived," Zia maintained.

According to Sultan Zia, the abductors were repeatedly saying that they were after Khalil for quite some time but they did not have a chance to get him.

Fazlur Rehman Khalil was one of the oldest jihadi leaders in Afghanistan, famed for fighting against the Soviets. He founded Harkat after the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan and fought alongside the mujahadeen forces.

Harkat was respected in jihadi circles for its role in the defeat of the communist Afghan Army of Afghanistan in the south-eastern Afghan province of Khost where the militant group then seized control in 1991. Khost was the first major city which fell to the mujahadeen fighters. The Harkat fighters also fought along side with the fugitive Taliban leader Maulana Jalaluddin Haqqani.

When the United States under the administration of Bill Clinton fired cruise missiles to target bin Laden in Afghanistan in 1998, Kandahar was attacked in a bid to kill the al-Qaeda leader and Khost was attacked to destroy the bases of the Harkat-ul-Mujahadeen in the province.

After the attacks, bin Laden held a press conference in Afghanistan, while at the same time Khalil held a separate press conference in Pakistan in which he supported bin Laden's statement to attack American interests all over the world. At the press conference, he also asserted that the Harkat-ul-Mujahadeen would take revenge on the US attack on Afghanistan.

After the 1998 attacks, Khalil also went on to hold many seminars in Pakistan in favour of bin Laden. The al-Qaeda leader provided him with large sums of money which he is believed to have embezzeled, after which he fell out of favour with bin Laden.

After the September 11, 2001 attacks on the United States, the FBI sought to interrogate him. It is believed they managed to do so and that Khalil was injected with various medicines which eventually affected his mental health. He often complained of physical problems as a result of the FBI interrogation

Sources said that although Khalil reportedly had abandoned all jihadi activities, the Pakistani authorities recently became suspicious about his activities and have interrogated him regarding his alleged ties with the Taliban fighters in the tribal region of Waziristan which borders Afghanistan.

(Syed Saleem Shahzad)

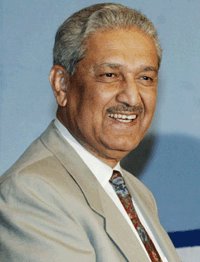

A Study of the A Q Khan Network

"The A.Q. Khan Network: Causes and Implications"

by Christopher O.Clary,

Naval Postgraduate School, December 2005

The activities of Pakistan's notorious Abdul Qadeer Khan in

proliferating nuclear weapons technology are examined in detail in a

recent Master's Thesis, along with an analysis of their enabling

conditions and some of their larger implications.

"The A. Q. Khan nuclear supplier network constitutes the most severe

loss of control over nuclear technology ever," wrote author

Christopher O. Clary.

"For the first time in history all of the keys to a nuclear weapon--

the supplier networks, the material, the enrichment technology, and

the warhead designs--were outside of state oversight and control."

"This thesis demonstrates that Khan's nuclear enterprise evolved out

of a portion of the Pakistani procurement network of the 1970s and

1980s. It presents new information on how the Pakistani state

organized, managed, and oversaw its nuclear weapons laboratories."

For Complete text click the title above:

President Carter on US - India nuclear deal

Dawn, March 30, 2006

A dangerous deal with India

By Jimmy Carter

DURING the past five years the United States has abandoned many of the nuclear arms control agreements negotiated since the administration of Dwight Eisenhower.

This change in policies has sent uncertain signals to other countries, including North Korea and Iran, and may encourage technologically capable nations to choose the nuclear option. The proposed nuclear deal with India is just one more step in opening a Pandora’s box of nuclear proliferation.

The only substantive commitment among nuclear-weapon states and others is the 1970 Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT), accepted by the five original nuclear powers and 182 other nations. Its key objective is “to prevent the spread of nuclear weapons and weapons technology ... and to further the goal of achieving nuclear disarmament.” At the five-year UN review conference in 2005, only Israel, North Korea, India and Pakistan were not participating — three with proven arsenals.

Our government has abandoned the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty and spent more than $80 billion on a doubtful effort to intercept and destroy incoming intercontinental missiles, with annual costs of about $9 billion. We have also forgone compliance with the previously binding limitation on testing nuclear weapons and developing new ones, with announced plans for earth-penetrating “bunker busters,” some secret new “small” bombs, and a move toward deployment of destructive weapons in space.

Another long-standing policy has been publicly reversed by our threatening first use of nuclear weapons against non-nuclear states. These decisions have aroused negative responses from NPT signatories, including China, Russia and even our nuclear allies, whose competitive alternative is to upgrade their own capabilities without regard to arms control agreements.

Last year former defence secretary Robert McNamara summed up his concerns in Foreign Policy magazine: “I would characterize current US nuclear weapons policy as immoral, illegal, militarily unnecessary, and dreadfully dangerous.”

It must be remembered that there are no detectable efforts being made to seek confirmed reductions of almost 30,000 nuclear weapons worldwide, of which the United States possesses about 12,000, Russia 16,000, China 400, France 350, Israel 200, Britain 185, India and Pakistan 40 each — and North Korea has sufficient enriched nuclear fuel for a half-dozen. A global holocaust is just as possible now, through mistakes or misjudgments, as it was during the depths of the Cold War.

Knowing for more than three decades of Indian leaders’ nuclear ambitions, I and all other presidents included them in a consistent policy: no sales of civilian nuclear technology or uncontrolled fuel to any country that refused to sign the NPT.

There was some fanfare in announcing that India plans to import eight nuclear reactors by 2012, and that US companies might win two of those reactor contracts, but this is a minuscule benefit compared with the potential costs. India may be a special case, but reasonable restraints are necessary. The five original nuclear powers have all stopped producing fissile material for weapons, and India should make the same pledge to cap its stockpile of nuclear bomb ingredients. Instead, the proposal for India would allow enough fissile material for as many as 50 weapons a year, far exceeding what is believed to be its current capacity.

So far India has only rudimentary technology for uranium enrichment or plutonium reprocessing, and Congress should preclude the sale of such technology to India. Former senator Sam Nunn said that the current agreement “certainly does not curb in any way the proliferation of weapons-grade nuclear material.” India should also join other nuclear powers in signing the Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty.

There is no doubt that condoning avoidance of the NPT encourages the spread of nuclear weaponry. Japan, Brazil, Indonesia, South Africa, Argentina and many other technologically advanced nations have chosen to abide by the NPT to gain access to foreign nuclear technology. Why should they adhere to self-restraint if India rejects the same terms? At the same time, Israel’s uncontrolled and unmonitored weapons status entices neighbouring leaders in Iran, Syria, Turkey, Saudi Arabia, Egypt and other states to seek such armaments, for status or potential use. The world has observed that among the “axis of evil,” nonnuclear Iraq was invaded and a perhaps more threatening North Korea has not been attacked.

The global threat of proliferation is real, and the destructive capability of irresponsible nations — and perhaps even some terrorist groups — will be enhanced by a lack of leadership among nuclear powers that are not willing to restrain themselves or certain chosen partners. Like it or not, the United States is at the forefront in making these crucial strategic decisions. A world armed with nuclear weapons could be a terrible legacy of the wrong choices. —Dawn/Washington Post Service

The writer is a former US president, a Democrat, and founder of the Carter Centre.

Wednesday, March 29, 2006

Afghanistan and the Logic of Suicide Bombing: A field study

How expatriates can help

Dawn, March 29, 2006

How expatriates can help

By Zubeida Mustafa

THE Pakistan Centre for Philanthropy (PCP), set up in 2001 as a non-profit support organisation to facilitate philanthropy, has published a report titled Philanthropy by the Pakistani Diaspora in the USA. Based on a survey it conducted in North America in which 631 Pakistani expatriates participated, this report confirms some trends that have been observed over the years.

It also makes some recommendations, though it is not at all clear if the obstacles faced in channelling philanthropy into an institutional charity in Pakistan can be overcome very easily.

Let us take the findings first which have been reported in more generous terms than how they emerge when read with a measure of objectivity. The PCP report describes the Pakistanis in North America — mainly professionals, quite a few being physicians and surgeons — as a “generous, giving and active community”. They donate 250 million dollars in cash and kind every year apart from 43.5 million hours of volunteered time which is given the monetary value of 750 million dollars by the PCP.

The report describes this amount (a total of one billion dollars) as “very impressive”. This is arguable. The cash and kind donations come to barely one per cent of the expatriates’ income. The time volunteered works out to 1.6 hours a week per head for the 500,000 migrants. It would be slightly more if you exclude the children.

But what cannot be denied is that in absolute terms the amount given as philanthropy is quite a big sum. It has, however, not made much of an impact nationally for several reasons. First, only a sum of 100 million dollars (40 per cent) actually comes to Pakistan. Secondly, most of this amount goes directly to individuals in need and not to institutionalized charities.

Hence the question to be asked is why are Pakistani expatriates not willing to give more generously to the country of their origin when they are in a position to do so? The most important factor is, to quote the report, “the chronic lack of trust in the civic sector in Pakistan; over 80 per cent of our survey respondents believe that such organisations are inefficient and dishonest; over 70 per cent feel that they are also ineffective and inattentive to the most pressing problems in Pakistan.”

One cannot deny that corruption is a bane in Pakistan and donors living in Pakistan also like to check before loosening their purse strings for an institution collecting donations. But that does not mean that there are no honest and efficient charities operating in the country that deserve to be helped.

What is understandable is that people living thousands of miles away find it difficult to obtain information about the performance of various institutions, hence they tend to be wary about giving. Information has never been the Pakistanis’ forte.

Another constraint faced by Pakistani Americans is the structural hurdles in transmitting money to Pakistan. After 9/11, American regulations were been tightened and are at times ambiguous about charitable giving abroad. Neither are there any convenient mechanisms to transfer funds to this country or to obtain information about a charity operating in Pakistan. Small wonder the kundi system has been so popular — its success can be attributed to its convenience and informal method.

Charities have also not been able to go about effectively in their fund raising mission. Some of them seeking donations from the expatriate community do not do their homework. They do not obtain exemption from taxes on donations — a powerful motivating factor — and that discourages many would-be philanthropists.

Experience shows that where an infrastructure is in place, funds flow in more easily. For instance, a few charitable organisations, which have representation abroad, are better known among the expatriates. They also manage to attract funds more easily. Thus the Layton Rehmatullah Benevolent Trust and the Edhi Foundation have successfully mobilized the Pakistani expatriate community for philanthropic causes. But this approach would benefit only large charities for small institutions cannot afford to have a representative in every country where Pakistani expatriates live.

In this context, the PCP offers some suggestions. The three key areas that must be addressed are

• Building confidence in Pakistan’s civic sector

• Facilitating mechanisms for charity giving

• Improving outreach on the achievements of the civic sector in Pakistan

Individual organizations can improve their prospects by adopting transparency in their working to inspire confidence in the public. They will also have to disseminate information about themselves. Many are already doing this yet they have failed to reach out effectively to many expatriates abroad given the considerable scope of the work involved.

The report suggests that the PCP could play a facilitating role by developing mechanisms for philanthropy. If the organization is not to become the conduit for funding — which it should not if it doesn’t want to lose its credibility — it should confine its role to being a clearing house of information and one providing guidance to philanthropists. Thus it should study the laws of different countries on the transmission of funds by the Pakistani diaspora to guide philanthropists on how to proceed. The organization could emerge as an important source of knowledge by giving essential but authentic facts about the various charities operating in the country. For instance a donor could be guided on how to do a quick check on a charity he wants to support. Some of the guidelines would be:

• determine the trustworthiness of a charity by checking its documentation

• obtain audited financial information

• study the profile of the organization

• look up the number of beneficiaries, their socio-economic status

• ask for the sources of income — are fees charged

This information should be enough to enable any intending expatriate donor to decide where he feels most comfortable about sending his donation.

The centre steps on sensitive ground when it speaks of the newly coined term “non-profit organization” (NPO). Does this suggest charity in the conventional old fashioned sense when people gave donations on humanitarian grounds? The idea was to help meet the basic needs — for food, health, shelter, education and livelihood — of a person who was unable to sustain himself on account of the failure of society to provide him social justice. But today organisations charging exorbitant fees for their services show themselves as NPOs because they show no profits in their accounts — their earnings being shown as their expenditure on keeping themselves functional. Are they deserving of philanthropy?

There is need to define ‘charity’. Under Indian law it is defined as including ‘relief of the poor — their education, health care and the advancement of any other object of general public utility’.

The PCP would do well to study the Indian diaspora’s giving pattern. India has a long tradition of philanthropy and its diaspora has made a big impact on India’s national life. Cultural traits determine a person’s approach to philanthropy and the Muslims of South Asia have not been known for it. A beginning could now be made.

The Pakistani diaspora in North America should be encouraged to make donations to the institutions that really cater to the needs of the poor. Many Americans of Pakistani origin have made a mark in life after graduating from public sector universities in Pakistan. Should they not repay their debt and help these universities in some way?

The health professionals who studied at the public sector medical colleges and are now doing so well in life should be helping their alma mater. After all, these are the institutions that really cater to the needs of the poor. One has to visit them to believe it.

As for the time the Pakistani diaspora volunteers could make an impact if people, especially health professionals and teachers, would return home every year to work for a few weeks to teach and train their own fellow professionals who are not affluent and could never hope to pay for good education abroad. The expatriates could finance the studies of a student who cannot pay for himself.

As for the PCP, it should encourage expatriates to play a direct role in supporting such institutions that really benefit the poor. The problem is that the rampant commercialism, that has overtaken the social sector in the hands of private entrepreneurs, has marginalised the poor. Even philanthropy seems to be sidelining them.

How expatriates can help

By Zubeida Mustafa

THE Pakistan Centre for Philanthropy (PCP), set up in 2001 as a non-profit support organisation to facilitate philanthropy, has published a report titled Philanthropy by the Pakistani Diaspora in the USA. Based on a survey it conducted in North America in which 631 Pakistani expatriates participated, this report confirms some trends that have been observed over the years.

It also makes some recommendations, though it is not at all clear if the obstacles faced in channelling philanthropy into an institutional charity in Pakistan can be overcome very easily.

Let us take the findings first which have been reported in more generous terms than how they emerge when read with a measure of objectivity. The PCP report describes the Pakistanis in North America — mainly professionals, quite a few being physicians and surgeons — as a “generous, giving and active community”. They donate 250 million dollars in cash and kind every year apart from 43.5 million hours of volunteered time which is given the monetary value of 750 million dollars by the PCP.

The report describes this amount (a total of one billion dollars) as “very impressive”. This is arguable. The cash and kind donations come to barely one per cent of the expatriates’ income. The time volunteered works out to 1.6 hours a week per head for the 500,000 migrants. It would be slightly more if you exclude the children.

But what cannot be denied is that in absolute terms the amount given as philanthropy is quite a big sum. It has, however, not made much of an impact nationally for several reasons. First, only a sum of 100 million dollars (40 per cent) actually comes to Pakistan. Secondly, most of this amount goes directly to individuals in need and not to institutionalized charities.

Hence the question to be asked is why are Pakistani expatriates not willing to give more generously to the country of their origin when they are in a position to do so? The most important factor is, to quote the report, “the chronic lack of trust in the civic sector in Pakistan; over 80 per cent of our survey respondents believe that such organisations are inefficient and dishonest; over 70 per cent feel that they are also ineffective and inattentive to the most pressing problems in Pakistan.”

One cannot deny that corruption is a bane in Pakistan and donors living in Pakistan also like to check before loosening their purse strings for an institution collecting donations. But that does not mean that there are no honest and efficient charities operating in the country that deserve to be helped.

What is understandable is that people living thousands of miles away find it difficult to obtain information about the performance of various institutions, hence they tend to be wary about giving. Information has never been the Pakistanis’ forte.

Another constraint faced by Pakistani Americans is the structural hurdles in transmitting money to Pakistan. After 9/11, American regulations were been tightened and are at times ambiguous about charitable giving abroad. Neither are there any convenient mechanisms to transfer funds to this country or to obtain information about a charity operating in Pakistan. Small wonder the kundi system has been so popular — its success can be attributed to its convenience and informal method.

Charities have also not been able to go about effectively in their fund raising mission. Some of them seeking donations from the expatriate community do not do their homework. They do not obtain exemption from taxes on donations — a powerful motivating factor — and that discourages many would-be philanthropists.

Experience shows that where an infrastructure is in place, funds flow in more easily. For instance, a few charitable organisations, which have representation abroad, are better known among the expatriates. They also manage to attract funds more easily. Thus the Layton Rehmatullah Benevolent Trust and the Edhi Foundation have successfully mobilized the Pakistani expatriate community for philanthropic causes. But this approach would benefit only large charities for small institutions cannot afford to have a representative in every country where Pakistani expatriates live.

In this context, the PCP offers some suggestions. The three key areas that must be addressed are

• Building confidence in Pakistan’s civic sector

• Facilitating mechanisms for charity giving

• Improving outreach on the achievements of the civic sector in Pakistan

Individual organizations can improve their prospects by adopting transparency in their working to inspire confidence in the public. They will also have to disseminate information about themselves. Many are already doing this yet they have failed to reach out effectively to many expatriates abroad given the considerable scope of the work involved.

The report suggests that the PCP could play a facilitating role by developing mechanisms for philanthropy. If the organization is not to become the conduit for funding — which it should not if it doesn’t want to lose its credibility — it should confine its role to being a clearing house of information and one providing guidance to philanthropists. Thus it should study the laws of different countries on the transmission of funds by the Pakistani diaspora to guide philanthropists on how to proceed. The organization could emerge as an important source of knowledge by giving essential but authentic facts about the various charities operating in the country. For instance a donor could be guided on how to do a quick check on a charity he wants to support. Some of the guidelines would be:

• determine the trustworthiness of a charity by checking its documentation

• obtain audited financial information

• study the profile of the organization

• look up the number of beneficiaries, their socio-economic status

• ask for the sources of income — are fees charged

This information should be enough to enable any intending expatriate donor to decide where he feels most comfortable about sending his donation.

The centre steps on sensitive ground when it speaks of the newly coined term “non-profit organization” (NPO). Does this suggest charity in the conventional old fashioned sense when people gave donations on humanitarian grounds? The idea was to help meet the basic needs — for food, health, shelter, education and livelihood — of a person who was unable to sustain himself on account of the failure of society to provide him social justice. But today organisations charging exorbitant fees for their services show themselves as NPOs because they show no profits in their accounts — their earnings being shown as their expenditure on keeping themselves functional. Are they deserving of philanthropy?

There is need to define ‘charity’. Under Indian law it is defined as including ‘relief of the poor — their education, health care and the advancement of any other object of general public utility’.

The PCP would do well to study the Indian diaspora’s giving pattern. India has a long tradition of philanthropy and its diaspora has made a big impact on India’s national life. Cultural traits determine a person’s approach to philanthropy and the Muslims of South Asia have not been known for it. A beginning could now be made.

The Pakistani diaspora in North America should be encouraged to make donations to the institutions that really cater to the needs of the poor. Many Americans of Pakistani origin have made a mark in life after graduating from public sector universities in Pakistan. Should they not repay their debt and help these universities in some way?

The health professionals who studied at the public sector medical colleges and are now doing so well in life should be helping their alma mater. After all, these are the institutions that really cater to the needs of the poor. One has to visit them to believe it.

As for the time the Pakistani diaspora volunteers could make an impact if people, especially health professionals and teachers, would return home every year to work for a few weeks to teach and train their own fellow professionals who are not affluent and could never hope to pay for good education abroad. The expatriates could finance the studies of a student who cannot pay for himself.

As for the PCP, it should encourage expatriates to play a direct role in supporting such institutions that really benefit the poor. The problem is that the rampant commercialism, that has overtaken the social sector in the hands of private entrepreneurs, has marginalised the poor. Even philanthropy seems to be sidelining them.

Tuesday, March 28, 2006

A Painful Narrative in NYT

Picture: Mukhtaran bibi

The New York Times

March 28, 2006 Tuesday

In Disgrace, And Facing Death By NICHOLAS D. KRISTOF

Aisha Parveen will live another day. Indeed, at least another week.

Ms. Parveen, the young Pashtun woman I wrote about on Sunday, was kidnapped at the age of 14 and imprisoned in a brothel here in southeastern Pakistan for six years. She escaped in January and married the man who helped her flee, but now a Pakistani court has charged her with adultery and is threatening to hand her back to the brothel owner -- even though she is adamant that he will then torture and kill her.

Ms. Parveen's court hearing was yesterday, and I was afraid that would be the end. But the court adjourned the case for one week for further investigation. And Ms. Parveen's lawyer thinks the mood is different now: the Pakistani press picked up on my column, and the attention will make judges more careful about handling her.

So the publicity may save her life, but it won't make much difference for thousands of other Aisha Parveens around the world. Asma Jahangir, the chairwoman of the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan, said she sees cases like Ms. Parveen's all the time.

''There is no such thing called justice in Pakistan,'' said Ms. Jahangir, a prominent lawyer in Lahore. ''It has simply collapsed.''

Ms. Jahangir fights heroically for poor women who have been charged -- like Ms. Parveen -- with zina offenses under Islamic law. Zina encompasses fornication and adultery, and accusations of zina are effective weapons against women.

Landlords often evict women tenants, for example, by accusing them of zina. Worse, women who go to the police to report rapes can be arrested for zina, because they have acknowledged illicit sex and yet usually cannot provide four male witnesses to prove that it was rape.

Even professionals like Ms. Jahangir are targeted if they confront the government. Last year, for example, the police attacked her and a group of other middle-class women demonstrating for women's rights. She says that an aide to President Pervez Musharraf gave the police instructions about her: ''Teach the [expletive] a lesson. Strip her in public.'' Sure enough, the police ripped off her shirt.

Ms. Parveen, now living in hiding after several kidnapping attempts in the last few days, faces an even more brutal struggle. Her only stroke of luck is having her new husband, Mohamed Akram, who rescued her from the brothel, on her side. The young couple are lovebirds, and each keeps talking about being so lucky to have found the other.

But Mr. Akram, while unwavering in his love, has disgraced his family by marrying a supposedly fallen woman, and his older sister is suffering.

''My brother-in-law sent me a message: 'Unless you divorce her, I will divorce your sister,' '' Mr. Akram lamented. ''She has two kids. And he's also beating her now. He's very upset because I married a girl who was in a brothel, who is not a virgin.''

The couple cannot seek refuge with Ms. Parveen's parents, because Pashtun parents routinely protect their family honor by killing daughters accused of zina.

''I cannot go back there because if I do, they'll kill me,'' Ms. Parveen said. ''In their eyes I'm dishonored, because even if a girl is kidnapped, then in their eyes she still should be killed.''

Saddest of all, her story isn't newsworthy in a classic sense. There's nothing at all unusual about a young Asian woman suffering years of sexual enslavement, or judicial malpractice or murder.

And that's the challenge for us all, Asians and Americans alike -- to change our worldview and put gender issues like sex trafficking higher on the global agenda.

A quarter-century ago, Jimmy Carter plucked human rights abuses from the backdrop of the international arena and put them on the agenda. Now it's time to focus on gender inequality in the developing world, for that is the greatest single source of human rights violations today.

Political dissidents tend to get the world's attention. But for every dissident who is beaten to death by government torturers somewhere in the world, thousands of ordinary women or girls die prematurely because of the effects of discrimination. In India, for example, girls 1 to 5 years old are 50 percent more likely to die than boys of the same age, because the boys are favored. That differential accounts for the death of a young Indian girl every four minutes.

Since these victims usually are voiceless, I'll give Ms. Parveen the last word so she can prick our consciences.

''God should not give daughters to poor people,'' she said in despair. ''And if a daughter is born, God should grant her death.''

Copyright 2006 The New York Times Company

Monday, March 27, 2006

Extremism of the Pakistani Expatriate

Daily Times, March 28, 2006

SECOND OPINION: The extremism of the expatriate — Khaled Ahmed’s TV Review

We are all aware that our brother Muslims living abroad, particularly in the secular West, have become intensely Islamic. This is quite natural when you are living abroad and wish to retain your identity. But religious extremism has cut two ways. Sectarian feelings are alive too and that should worry us.

Digital TV (February 8, 2006) showed clerics in the UK discussing Muharram in a spirit of Shia-Sunni amity. They highlighted the common points of devotion in both sects. The programme was interactive. When the calls came in they were mostly Sunnis raising objections to the Shia faith. The clerics on the show kept reminding the callers of the goodwill-orientation of the programme but the callers insisted on asking about the “fact” that the Shias had killed Ali and his offspring and that the narrative of Karbala was not real but concocted.

GEO TV (February 9, 2006) faced the problem of identifying Yazid today. The politicians kept identifying each other as Yazid while the combined opposition identified Musharraf as Yazid.

It is obvious that the callers were deep into the Shia-Sunni rift and were quite taken up with their “new knowledge” of the heresy of the sect. Their knowledge was acquired from the cleric in the mosque and religious discourse at home. Once again the dominance on them of Arab Islam was clear. The Shia callers did not ring because of the presumed prejudice of the channel, which was in fact airing a non-sectarian worldview.

The switchover from Barelvi Islam to Deobandi Islam in the UK has resulted in the conversion of the mystically minded Kashmiri expatriates to hardline Muslims. The reason was import of wrong mullahs from Pakistan by the UK government and by the influence wielded on the mosques by rich Arabs scholars. Back in Pakistan the person of Yazid was being abused for the service of a brand of politics that lacks morality.

BBC (February 8, 2006) re-ran its interview with Abu Hamza al Masari who was sentenced to seven years in prison in the UK for inciting people to terrorism. Out in the streets, BBC showed Al Masari’s supporters condemning the British Muslim Council for not favouring the vandalism of Muslims in the UK protesting against Danish cartoons. The protest was led by a Pakistani Muslim Anjum Chaudhry speaking for Al Fuqara organisation. Anjum Chaudhry was condemning the sentencing of Abu Hamza al Masari.

Al Fuqara was/is the outfit run by Gilani who trained the British shoe-bomber Reid who was sent by Al Masari to Pakistan for training. Journalist Daniel Pearl was trying to meet Gilani in Karachi when he was killed.

Labbaik TV Channel (February 9, 2006) had Allama Tahir ul Qadiri lecturing on the sacrifice of Imam Husain. He said Muhammad (peace be upon him) was created before the creation of the Universe. Allah did hamd and Muhammad was created. Then Muhammad did hamd and Ahmad was created. When Allah loved, Mustafa was created. Hasan and Husain as names were coined in Paradise. These names had never appeared among the Arabs in pre-Islamic times.

This was a good programme by a Sunni scholar. Typically a Barelvi scholar like Mr Qadiri will reach out and try to play down the sectarian rift. His audience was mixed because Barelvis and the Shia are known to mix better than Shia with Deobandi. In the Digital TV discussion and BBC news referred to above, the Barelvi influence in the UK appeared to be definitely in decline.

ARY (February 9, 2006) Dr Shahid Masud asked Oriya Maqbool Jan if the riots in the Muslim world had scared the Europeans sufficiently about the Danish cartoons. Oriya said the Europeans had got scared of the Muslims but the Muslims of the world should unite and collectively boycott the West and inflict economic damage on it. He lamented the fact that the rulers of Pakistan were not sufficiently naraz (angry) with Europe. The narazgi (anger) of the people was not officially expressed by the governments the way it should have been.

The presumption here is that the violence resorted to by Muslims in their own countries will somehow scare the Europeans. Why should the Europeans be scared of us while we kill ourselves and destroy our own property? The argument here is quite convoluted. It goes like this. The European civilisation is based on humanism and therefore tends to be feminine as opposed to our own which is masculine. The Europeans have the tendency to cringe when they see violence even to their enemies. Hence, let us kill ourselves to make the Europeans cringe and finally surrender.

HUM TV (February 12, 2006) Naeem Bukhari talked to Rahat Kazmi about his life and times. Rahat recalled that to get married to Sahira he had to become a civil servant. He got in together with his two other friends Aitzaz Ahsan and late Asif Sajjad Jan, but the two did not join the academy as he did. Later he too ducked out. Rahat spoke about his career in the films and then on TV as an actor in plays when they reached their climax. The show was frank and sincere.

Rahat Kazmi is one of a group of rare persons in Pakistan who have developed as deeply cultured human beings. As an actor, his grasp of the Urdu language is correct. His civilisational perspective is inclusive rather than paranoid. People like him make one wonder why most actors are so inarticulate in contrast? A true actor will always be (or should be) a great communicator. *

SECOND OPINION: The extremism of the expatriate — Khaled Ahmed’s TV Review

We are all aware that our brother Muslims living abroad, particularly in the secular West, have become intensely Islamic. This is quite natural when you are living abroad and wish to retain your identity. But religious extremism has cut two ways. Sectarian feelings are alive too and that should worry us.

Digital TV (February 8, 2006) showed clerics in the UK discussing Muharram in a spirit of Shia-Sunni amity. They highlighted the common points of devotion in both sects. The programme was interactive. When the calls came in they were mostly Sunnis raising objections to the Shia faith. The clerics on the show kept reminding the callers of the goodwill-orientation of the programme but the callers insisted on asking about the “fact” that the Shias had killed Ali and his offspring and that the narrative of Karbala was not real but concocted.

GEO TV (February 9, 2006) faced the problem of identifying Yazid today. The politicians kept identifying each other as Yazid while the combined opposition identified Musharraf as Yazid.

It is obvious that the callers were deep into the Shia-Sunni rift and were quite taken up with their “new knowledge” of the heresy of the sect. Their knowledge was acquired from the cleric in the mosque and religious discourse at home. Once again the dominance on them of Arab Islam was clear. The Shia callers did not ring because of the presumed prejudice of the channel, which was in fact airing a non-sectarian worldview.

The switchover from Barelvi Islam to Deobandi Islam in the UK has resulted in the conversion of the mystically minded Kashmiri expatriates to hardline Muslims. The reason was import of wrong mullahs from Pakistan by the UK government and by the influence wielded on the mosques by rich Arabs scholars. Back in Pakistan the person of Yazid was being abused for the service of a brand of politics that lacks morality.

BBC (February 8, 2006) re-ran its interview with Abu Hamza al Masari who was sentenced to seven years in prison in the UK for inciting people to terrorism. Out in the streets, BBC showed Al Masari’s supporters condemning the British Muslim Council for not favouring the vandalism of Muslims in the UK protesting against Danish cartoons. The protest was led by a Pakistani Muslim Anjum Chaudhry speaking for Al Fuqara organisation. Anjum Chaudhry was condemning the sentencing of Abu Hamza al Masari.

Al Fuqara was/is the outfit run by Gilani who trained the British shoe-bomber Reid who was sent by Al Masari to Pakistan for training. Journalist Daniel Pearl was trying to meet Gilani in Karachi when he was killed.

Labbaik TV Channel (February 9, 2006) had Allama Tahir ul Qadiri lecturing on the sacrifice of Imam Husain. He said Muhammad (peace be upon him) was created before the creation of the Universe. Allah did hamd and Muhammad was created. Then Muhammad did hamd and Ahmad was created. When Allah loved, Mustafa was created. Hasan and Husain as names were coined in Paradise. These names had never appeared among the Arabs in pre-Islamic times.

This was a good programme by a Sunni scholar. Typically a Barelvi scholar like Mr Qadiri will reach out and try to play down the sectarian rift. His audience was mixed because Barelvis and the Shia are known to mix better than Shia with Deobandi. In the Digital TV discussion and BBC news referred to above, the Barelvi influence in the UK appeared to be definitely in decline.

ARY (February 9, 2006) Dr Shahid Masud asked Oriya Maqbool Jan if the riots in the Muslim world had scared the Europeans sufficiently about the Danish cartoons. Oriya said the Europeans had got scared of the Muslims but the Muslims of the world should unite and collectively boycott the West and inflict economic damage on it. He lamented the fact that the rulers of Pakistan were not sufficiently naraz (angry) with Europe. The narazgi (anger) of the people was not officially expressed by the governments the way it should have been.

The presumption here is that the violence resorted to by Muslims in their own countries will somehow scare the Europeans. Why should the Europeans be scared of us while we kill ourselves and destroy our own property? The argument here is quite convoluted. It goes like this. The European civilisation is based on humanism and therefore tends to be feminine as opposed to our own which is masculine. The Europeans have the tendency to cringe when they see violence even to their enemies. Hence, let us kill ourselves to make the Europeans cringe and finally surrender.

HUM TV (February 12, 2006) Naeem Bukhari talked to Rahat Kazmi about his life and times. Rahat recalled that to get married to Sahira he had to become a civil servant. He got in together with his two other friends Aitzaz Ahsan and late Asif Sajjad Jan, but the two did not join the academy as he did. Later he too ducked out. Rahat spoke about his career in the films and then on TV as an actor in plays when they reached their climax. The show was frank and sincere.

Rahat Kazmi is one of a group of rare persons in Pakistan who have developed as deeply cultured human beings. As an actor, his grasp of the Urdu language is correct. His civilisational perspective is inclusive rather than paranoid. People like him make one wonder why most actors are so inarticulate in contrast? A true actor will always be (or should be) a great communicator. *

Sunday, March 26, 2006

Pakistani Dilemma: A Perspective

Harvard Political Review, Spring 2006

Pakistani Dilemma:America’s uneasy ally searches for a way forward

By BECCA FRIEDMAN

Pakistan’s President Pervez Musharraf is in trouble. Since seizing power in a military coup in October 1999, Musharraf has been trying to lead the country toward stability and modernization. Beleaguered by problems ranging from a sluggish economy to Islamist extremism to tense relations with India, many Pakistanis initially looked at Musharraf’s administration as a positive force for change. And after September 11, Musharraf became an important ally to the United States in the War on Terror. But today his authority is growing more precarious and his future is in doubt. Ensuring a lasting alliance with Pakistan will require the United States to disentangle itself from the embattled leader and build an institutionalized bilateral relationship that can survive a power turnover.

Ambivalent Ally

For the United States , the greatest geo-strategic benefit of an alliance with Pakistan lies in its ability to play a progressive role in a turbulent region. Hassan Abbas, a former official in the last two presidential administrations, explained to the HPR that Pakistan "has a strong army, a history of democracy, and it has potential… we need more Islamic countries on the side of progressivism instead of dogmatism… with the proper nurturing, Pakistan can be a very positive country for the U.S. as an ally 20 to 25 years down the line.” But recent developments make it clear that such a future will not be realized under Musharraf’s leadership.

Since taking power, America’s partnership with Musharraf centered on his willingness to respond to U.S. demands to crack down on terrorist organizations within Pakistani borders. It seems, however, that Musharraf has not upheld his end of the bargain, largely because he has a political interest in the continued existence of radical Muslim groups. Vali Nasr, a Pakistan expert at the Council on Foreign Relations, told the HPR that Musharraf “has been tough… on Arab extremists, but he has been soft on domestic extremists… [The Taliban] was a way to influence and control Afghanistan; extremists were a way to put Kashmir on the boiler… These groups are like weapons systems for Pakistan, they won’t give them up that easily.”

In fact, Islamic radicals offer crucial support in Musharraf’s continued campaign to marginalize the liberal parties, who pose the biggest threat to his power and legitimacy. Abbas explained that if there were a transparent election today, Musharraf would lose to exiled progressive leaders such as former Prime Ministers Benazir Bhutto and Nawaz Sharif. The Pakistani people, it seems, are suffering from authoritarian fatigue after seven years of military rule.

Troubled Times Ahead

Beset by difficulties, Musharraf faces many challenges without clear-cut solutions. Tensions in Baluchistan, the poorest of Pakistan’s four provinces, have erupted into violence over the tribal people’s claims to a greater portion of the profits from their natural gas and mineral wealth. Joint Chinese-Pakistani cooperation on a new port in Gwadar has further incited rebellion, as Baluch radicals demand a share in the profits. These developments are troubling to America: stability in Baluchistan is paramount for the War on Terror; it lies on the border with Afghanistan and is a haven for al-Qaeda and Taliban militants. Cooperation with China might mean an increased Chinese presence in Pakistan’s affairs.

A disgruntled America is in turn deeply troubling for Musharraf, as American support has long played a crucial role in sustaining his regime. Stephen Cohen of the Brookings Institute told the HPR that the government in Islamabad is receiving huge amounts of aid for cooperation in the War on Terror. But there are indications that even Washington is losing faith in Musharraf’s capability. Christine Fair, a specialist on South Asia at the U.S. Institute of Peace, told the HPR that the manner in which the military conducted recent American air strikes in northern Pakistan signals a changing attitude. Whereas before Musharraf would have received political cover for what would obviously be a domestically contentious issue, such assistance was not forthcoming from Washington.

For the near future, his support from Pakistan’s armed forces ensures Musharraf’s continued rule. To overthrow the dictatorship would take “either serious dissent within the military – and Musharraf has purged the military repeatedly to make sure that that doesn’t happen – or you need a serious uprising to challenge the military in the street,” according to Nasr. Despite some vociferous dissent, such revolutionary circumstances are not yet at hand in Pakistan.

Despite their misgivings, Washington must be careful not to undermine Musharraf without a better plan for stability. Anti-Americanism is high in Pakistan, especially among the most powerful opposition groups in Parliament. After Musharraf – a leader with a looming expiration date – Fair believes that for the alliance to continue, American and Pakistani interests must be realigned. She calls for “a complete and total overlap of interests… vis a vis security in South Asia, Afghanistan, [and] security in Pakistan.” If this is unachievable in the foreseeable future, both the United States and Musharraf will have to hold on and hope for the best.

"Moderate Versus Radical Islam": A Perspective

Dawn, March 24, 2006

‘Moderate’ vs. radical Islam

By Ayaz Amir

FEW words today carry a more negative meaning than the term Taliban. It is supposed to stand for everything backward, reactionary and benighted: harsh punishments, the seclusion of women and a mindset conducive to the promotion of ‘terrorism’.

Opposed to Talibanism is something called ‘moderate’ Islam which is supposed to stand for progress and enlightenment. Since September 11 the United States has been spending huge sums of money (ask US-Aid) in this battle of ideas, denouncing ‘extremism’ and promoting a fuzzy picture of ‘moderate’ Islam.

Whether it is meeting with any success in this battle is hard to say because the US has never been more unpopular in the Islamic world. Most rulers of Muslim countries may be America’s friends, if not its satellites, but at the level of popular opinion it doesn’t take much to realize that anti-Americanism is on the rise.

Much of this has to do with American double standards. American atrocities in Afghanistan and Iraq, of which there has been no shortage since the invasion of both countries, is all for the good, part of a grand design to promote democracy. Resisting American aggression and occupation is ‘terrorism’.

Dishonesty up to a point is perhaps bearable but when it crosses all limits and becomes a daily occurrence don’t be surprised if the reaction is outrage.

Every time President Bush appears on television and speaks on Iraq it is possible to visualize some more Arabs or Muslims going over to the anti-American camp. Al-Qaeda doesn’t have to stoke anti-American feelings. The Bush administration does that job better than anyone else.

Regarding the Taliban, however, it is easy to be critical about them, less easy to say a word in their praise. But some things stand out and are difficult to ignore.

For instance, for all their narrow-minded interpretation of Islam, the Taliban at least have the courage of their convictions. Many of us supporters may not agree with the austerity and rigour of their doctrine. But it is hard not to admire their courage and tenacity. Against all the odds they are still fighting the Americans and, hard though it may have been to imagine this four years ago, getting stronger by the day.

The best that so-called Islamic ‘moderates’ seem capable of is to curry favour with the US. The long-bearded narrow-mindedness of the Taliban may be frightening but the fawning attitude of the ‘moderates’ is sickening. The Taliban may be too rigid but so-called moderates are too spineless and seem to lack all conviction.

Post-September 11 the US asked the Taliban leadership of Afghanistan to hand over Sheikh Osama bin Laden. Mullah Omar, the Taliban Emir, refused, saying that any charges against bin Laden could be examined by an ‘independent tribunal’. Call the Taliban foolhardy but at least they did not deliver a guest, and an honoured one at that, to his enemies.

Contrast this with our attitude. Mullah Zareef was the Taliban’s accredited ambassador to Pakistan and as such under our protection. But when the Americans asked for him our military government handed him over without a moment’s hesitation. Come to think of it, hardly something to be proud of.

Would the Americans have been impressed? More likely, they would have caught the impression that the Pakistani leadership could be pushed around. No wonder, they have been pushing it ever since.

Avoiding stupidity or rashness, we should have stayed neutral in the impending conflict over Afghanistan. We had no choice but to cut our links with the Taliban. But our military whiz kids went beyond the dictates of prudence and caution. Far from staying neutral, they offered forward bases and other facilities to the Americans. This was uncalled for and went against the sentiments of most Pakistanis.

The argument given was that Pakistan was being saved. In fact, the military government was saving its own skin, ending its international isolation and getting a new lease of life.

No one is saying, and certainly not I, that we should have followed the path of the Taliban. But it would have done us no harm if we could have borrowed some of their resolve. The Taliban are fighting a difficult war from the mountains but they are still their own masters. They have lost power and much else besides but not their self-respect. Mullah Omar, hiding God knows where, remains as defiant as ever.

We have a huge military, nuke capability and all sorts of missiles named after our vaunted heroes: Ghauri, Abdali and, most recently, Babur. (Although Abdali, incidentally, is a poor choice. Despite being the victor of the third battle of Panipat, his repeated invasions of Punjab caused much devastation and suffering.) But of what use all this military muscle when it does nothing to strengthen self-confidence?

Clinton as president comes here for a few hours and ends up insulting us. Bush comes here and there is more humiliation flung our way despite all the services Pakistan’s military rulers are rendering in the fight against al-Qaeda and the Taliban. Nukes and missiles are not of much help in such a situation.

We don’t have to seek US hostility. But we can also avoid unnecessary toadying. And we must learn to think for ourselves, which we won’t do unless we get out of the American orbit in which we have revolved for too long.

The demonizing of Islam after September 11 has gone far enough. We don’t have to be apologetic about Islam or fall for the American-inspired dialectic of ‘moderate’ and ‘radical’ Islam. As far as the Americans are concerned, any Muslim country toeing the American line is moderate. Any Muslim country standing up for itself is radical.

There is nothing wishy-washy about Islam. The essence of the faith as propagated by Muhammad, (Peace be upon him), is radical and revolutionary. Stripped off the time-serving interpretations of theologians (theologians being the bane of Islam) it stands for the empowerment of the weak, the humbling of the mighty, the liberation of women, government by consent and consultation, and bread, security, learning and hospitals for every citizen, high or low, of the Islamic commonwealth.

The Islam of the Prophet is a fusion (never attempted before or since) of two great principles, socialism and democracy. The spirit of this fusion was best expressed by Hazrat Omar when he said that even if a dog went hungry by the banks of the Euphrates (some distance from Makkah, the Islamic capital) Omar would have to answer for this on the Day of Judgment. And by Hazrat Ali when he said that a tyranny, even if covered in the mantle of Islam can never endure. There’s nothing ‘moderate’ about these thoughts. They are radical to the core.

Lest anyone be in a hurry to revive that tired chestnut of Islam being opposed to reason and learning, let me quote a few lines from William Dalrymple’s excellent essay, Inside the Madrasas (New York Review, December1, 2005):

“In The Rise of Colleges: Institutions of Learning in Islam and the West, George Makdisi has demonstrated how terms such as having ‘fellows’ holding a ‘chair’, or students ‘reading’ a subject and obtaining ‘degrees’, as well as practices such as inaugural lectures, the oral defence, even mortar boards, tassels, and academic robes, can all be traced back to the practices of the madrasas.” (There is more on the same lines in the rest of the essay.)

Nothing is funnier than the frequently heard assertion that people associated with al Qaeda are madmen who hate the western worlds wealth and freedoms. To quote Dalrymple again: “As (bin Laden) laconically remarked in his broadcast timed to coincide with the last US election, if it was freedom they were against, al Qaeda would have attacked Sweden.”

Agree or disagree with Osama bin Laden’s tactics, his aims are intensely political: an end to American hegemony over the world of Islam, justice for the Palestinian people, the toppling of ‘apostate’ regimes subservient to America. Al Qaeda may be inspired by Islam but it is not a religious organization in the strict sense of that term. What it stands for and what it strives to achieve is a response, primarily, to the excesses and double standards of American foreign policy in relation to the world of Islam. Ignoring this sequence of cause-and-effect is both misleading and dishonest.

‘Moderate’ vs. radical Islam

By Ayaz Amir

FEW words today carry a more negative meaning than the term Taliban. It is supposed to stand for everything backward, reactionary and benighted: harsh punishments, the seclusion of women and a mindset conducive to the promotion of ‘terrorism’.

Opposed to Talibanism is something called ‘moderate’ Islam which is supposed to stand for progress and enlightenment. Since September 11 the United States has been spending huge sums of money (ask US-Aid) in this battle of ideas, denouncing ‘extremism’ and promoting a fuzzy picture of ‘moderate’ Islam.

Whether it is meeting with any success in this battle is hard to say because the US has never been more unpopular in the Islamic world. Most rulers of Muslim countries may be America’s friends, if not its satellites, but at the level of popular opinion it doesn’t take much to realize that anti-Americanism is on the rise.

Much of this has to do with American double standards. American atrocities in Afghanistan and Iraq, of which there has been no shortage since the invasion of both countries, is all for the good, part of a grand design to promote democracy. Resisting American aggression and occupation is ‘terrorism’.

Dishonesty up to a point is perhaps bearable but when it crosses all limits and becomes a daily occurrence don’t be surprised if the reaction is outrage.

Every time President Bush appears on television and speaks on Iraq it is possible to visualize some more Arabs or Muslims going over to the anti-American camp. Al-Qaeda doesn’t have to stoke anti-American feelings. The Bush administration does that job better than anyone else.

Regarding the Taliban, however, it is easy to be critical about them, less easy to say a word in their praise. But some things stand out and are difficult to ignore.

For instance, for all their narrow-minded interpretation of Islam, the Taliban at least have the courage of their convictions. Many of us supporters may not agree with the austerity and rigour of their doctrine. But it is hard not to admire their courage and tenacity. Against all the odds they are still fighting the Americans and, hard though it may have been to imagine this four years ago, getting stronger by the day.

The best that so-called Islamic ‘moderates’ seem capable of is to curry favour with the US. The long-bearded narrow-mindedness of the Taliban may be frightening but the fawning attitude of the ‘moderates’ is sickening. The Taliban may be too rigid but so-called moderates are too spineless and seem to lack all conviction.

Post-September 11 the US asked the Taliban leadership of Afghanistan to hand over Sheikh Osama bin Laden. Mullah Omar, the Taliban Emir, refused, saying that any charges against bin Laden could be examined by an ‘independent tribunal’. Call the Taliban foolhardy but at least they did not deliver a guest, and an honoured one at that, to his enemies.

Contrast this with our attitude. Mullah Zareef was the Taliban’s accredited ambassador to Pakistan and as such under our protection. But when the Americans asked for him our military government handed him over without a moment’s hesitation. Come to think of it, hardly something to be proud of.

Would the Americans have been impressed? More likely, they would have caught the impression that the Pakistani leadership could be pushed around. No wonder, they have been pushing it ever since.

Avoiding stupidity or rashness, we should have stayed neutral in the impending conflict over Afghanistan. We had no choice but to cut our links with the Taliban. But our military whiz kids went beyond the dictates of prudence and caution. Far from staying neutral, they offered forward bases and other facilities to the Americans. This was uncalled for and went against the sentiments of most Pakistanis.

The argument given was that Pakistan was being saved. In fact, the military government was saving its own skin, ending its international isolation and getting a new lease of life.

No one is saying, and certainly not I, that we should have followed the path of the Taliban. But it would have done us no harm if we could have borrowed some of their resolve. The Taliban are fighting a difficult war from the mountains but they are still their own masters. They have lost power and much else besides but not their self-respect. Mullah Omar, hiding God knows where, remains as defiant as ever.

We have a huge military, nuke capability and all sorts of missiles named after our vaunted heroes: Ghauri, Abdali and, most recently, Babur. (Although Abdali, incidentally, is a poor choice. Despite being the victor of the third battle of Panipat, his repeated invasions of Punjab caused much devastation and suffering.) But of what use all this military muscle when it does nothing to strengthen self-confidence?

Clinton as president comes here for a few hours and ends up insulting us. Bush comes here and there is more humiliation flung our way despite all the services Pakistan’s military rulers are rendering in the fight against al-Qaeda and the Taliban. Nukes and missiles are not of much help in such a situation.

We don’t have to seek US hostility. But we can also avoid unnecessary toadying. And we must learn to think for ourselves, which we won’t do unless we get out of the American orbit in which we have revolved for too long.

The demonizing of Islam after September 11 has gone far enough. We don’t have to be apologetic about Islam or fall for the American-inspired dialectic of ‘moderate’ and ‘radical’ Islam. As far as the Americans are concerned, any Muslim country toeing the American line is moderate. Any Muslim country standing up for itself is radical.

There is nothing wishy-washy about Islam. The essence of the faith as propagated by Muhammad, (Peace be upon him), is radical and revolutionary. Stripped off the time-serving interpretations of theologians (theologians being the bane of Islam) it stands for the empowerment of the weak, the humbling of the mighty, the liberation of women, government by consent and consultation, and bread, security, learning and hospitals for every citizen, high or low, of the Islamic commonwealth.

The Islam of the Prophet is a fusion (never attempted before or since) of two great principles, socialism and democracy. The spirit of this fusion was best expressed by Hazrat Omar when he said that even if a dog went hungry by the banks of the Euphrates (some distance from Makkah, the Islamic capital) Omar would have to answer for this on the Day of Judgment. And by Hazrat Ali when he said that a tyranny, even if covered in the mantle of Islam can never endure. There’s nothing ‘moderate’ about these thoughts. They are radical to the core.

Lest anyone be in a hurry to revive that tired chestnut of Islam being opposed to reason and learning, let me quote a few lines from William Dalrymple’s excellent essay, Inside the Madrasas (New York Review, December1, 2005):

“In The Rise of Colleges: Institutions of Learning in Islam and the West, George Makdisi has demonstrated how terms such as having ‘fellows’ holding a ‘chair’, or students ‘reading’ a subject and obtaining ‘degrees’, as well as practices such as inaugural lectures, the oral defence, even mortar boards, tassels, and academic robes, can all be traced back to the practices of the madrasas.” (There is more on the same lines in the rest of the essay.)

Nothing is funnier than the frequently heard assertion that people associated with al Qaeda are madmen who hate the western worlds wealth and freedoms. To quote Dalrymple again: “As (bin Laden) laconically remarked in his broadcast timed to coincide with the last US election, if it was freedom they were against, al Qaeda would have attacked Sweden.”